If you are a contractor or a homeowner working with a contractor, it’s important to know about builders’ liens.

This page provides general legal information about builders' liens under Nova Scotia's Builders’ Lien Act, including:

- what liens are and

- how to register, enforce or dispute a lien.

A lien is a type of security. Anyone who performs work on or supplies materials to someone else’s land can register a builders’ lien against that land as security for getting paid. Contractors can register liens on various construction projects, including building and renovating homes.

Once registered at the appropriate Land Registration Office, a builder’s lien affects the owner’s interest in the property and can interfere with selling or mortgaging the property.

Each province has builders’ lien legislation that gives this remedy to suppliers and contractors, and each law is slightly different. This page only discusses Nova Scotia’s law, so if you have worked on a property outside Nova Scotia, you must look at the legislation in that province, territory or other place.

This information does not replace legal advice from a lawyer. Liens are very technical and complicated. We recommend hiring a lawyer if you are considering registering a lien or if a contract or sub-contractor has registered a lien against your property.

What is a builders’ lien?

A builders’ lien is a remedy for anyone who supplies materials, provides services, or performs work that improves someone else’s land.

Builders’ liens aim to fill a gap in the common law (law from court decisions) that negatively affects contractors and suppliers on construction projects. Suppliers and contractors often work on a property and then have trouble getting paid. Suppliers and contractors have a common law claim for breach of contract against whoever they had a direct contract with. They could sue whoever agreed to pay them for their work. But, often, the property owner was not the one they had a contract with and not the one who agreed to pay them. Instead, their agreement may be with another contractor supervising their work on the project (this type of contractor is called a general contractor).

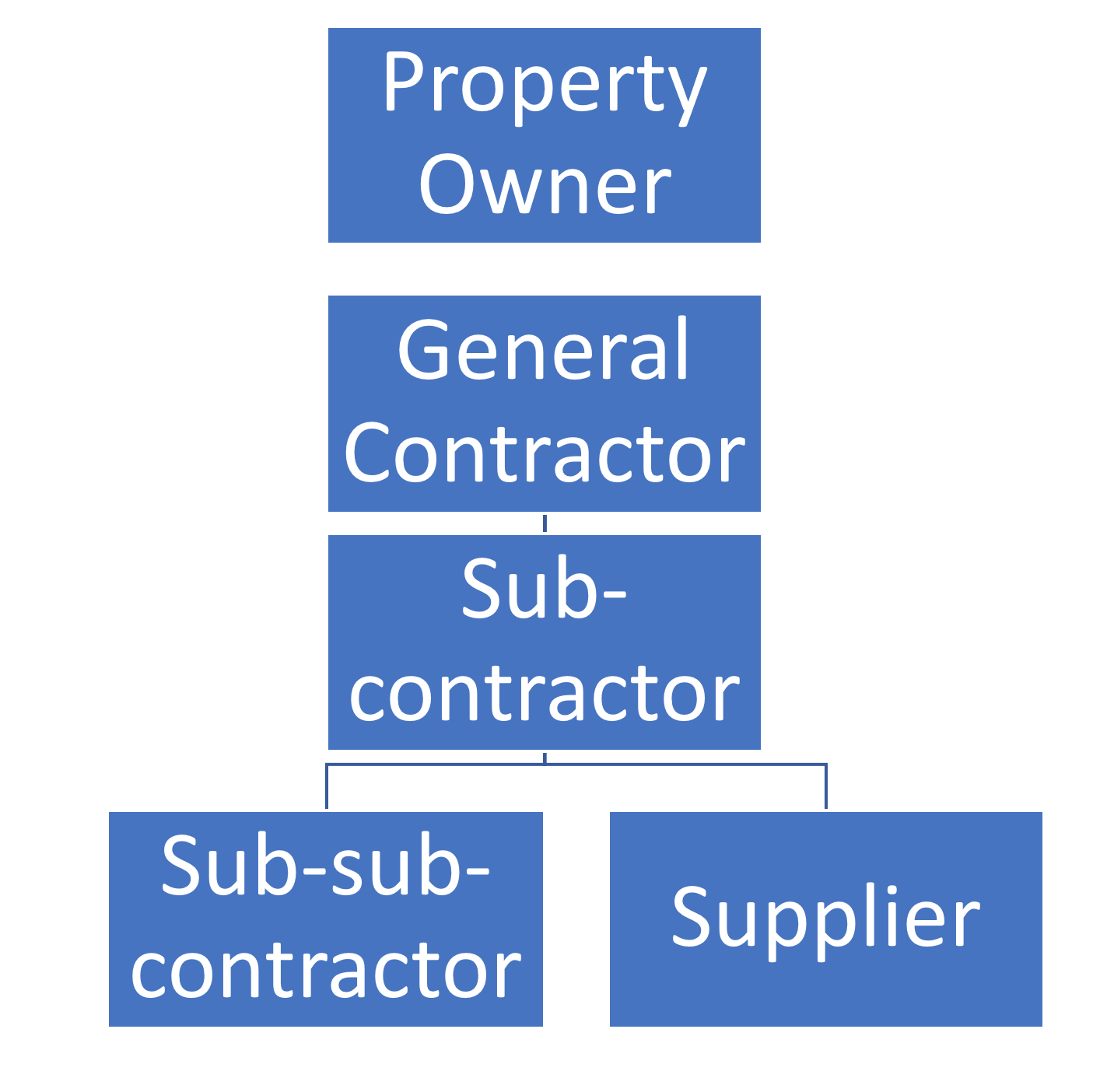

It is very common in construction projects, and particularly larger projects such as building a new home from scratch, to have what is called a ‘construction chain’ where the owner contracts with a general contractor, who in turn contracts with sub-contractors, who in turn contract with sub-sub-contractors and suppliers (see figure).

It is very common in construction projects, and particularly larger projects such as building a new home from scratch, to have what is called a ‘construction chain’ where the owner contracts with a general contractor, who in turn contracts with sub-contractors, who in turn contract with sub-sub-contractors and suppliers (see figure).

This construction chain can create a situation where a sub-contractor performs work on a project without getting paid by the general contractor. This could be for several reasons, such as the general contractor not being well organized or being bankrupt or insolvent. Whatever the reason, while the sub-contractor has a valid breach of contract claim against the general contractor because she has a direct contract with them, she does not have any common law claim against anyone else in the construction chain, such as the owner, even though her work helped improve the owner’s land. The same applies to sub-sub-contractors: they may have a direct contract with the sub-contractor but not the owner or general contractor, even though their work improved the owner’s land and helped the general contractor get the work done well and on time.

That is where liens under the Builders' Lien Act come in. A lien allows the unpaid contractor or supplier to register a lien against the owner’s property in the amount they are owed for their work and then claim the outstanding amount from the owner and anyone between them and the owner in the construction chain. The lien acts as security for payment in that, once registered against the owner’s property, it interferes with the owner’s ability to sell or mortgage the property. Property owners cannot refinance or sell their property without first removing the lien from the property by paying the contractor who registered it. Liens, therefore, provide a valuable tool for contractors and suppliers to pursue payment for work they have done on a property.

For contractors, subcontractors, suppliers and labourers

Who can file a builders’ lien?

A lien may be filed by anyone who worked on, provided services, or supplied materials for a certain property. This typically includes:

- a general contractor

- subcontractors, sub-sub-contractors, etc

- suppliers; and

- labourers.

Architects, engineers, and surveyors may also file liens if their work or services directly relate to the specific piece of land.

If you do not fall into one of these categories, speak to a lawyer. There may still be a way for you to register a lien or another way to make a claim for money owed.

Before you start - basic steps to bring a lien claim

Time limits are critical in making a lien claim. You must strictly follow the timelines and requirements for registering liens and proving a lien claim. The timelines are in the Builders' Lien Act. If you miss a deadline, you may not be able to put a lien on the owner’s property, and you will not be able to prove your lien claim.

There are several steps to bring a lien claim:

Step 1. Register the lien against the property at the Land Registry

Step 2. Start a legal action in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia against everyone above the contractor or supplier in the construction chain

Step 3. Register the action with the Land Registry.

The following three sections discuss each step and the strict timelines and requirements under each step. You must complete steps 2 and 3 simultaneously.

Before registering a lien, contractors should also consider whether registering it may prompt the owner to bring an action against them regarding the work. For example, they may allege that your work was defective and that they had to pay another contractor to fix it, and they may claim against you for the costs of hiring the other contractor. It is therefore essential to consider:

- are there any possible deficiencies in your work that would cause the owner to claim against you?

- whether the risks of starting a lien claim are worth triggering a counterclaim that could exceed the amount of your lien claim.

Of course, an owner may still claim against you even if you do not register a lien. However, filing a lien often prompts an owner who was otherwise willing to move on to file a claim.

Step 1 How do I register a lien?

You will need assistance from a lawyer to register a lien.

The lawyer will register the lien against the property at the appropriate Land Registry.

You must register the lien within 60 calendar days after the last day the contractor worked on or delivered materials to the property.

It is vitally important to record each day you work on a project and the nature of the work you performed that day, as you will need to know the last day you worked on a project to know when the deadline for registering your lien will expire. Court decisions have said that the last day of work does not include work performed to fix or repair work already done.

Speak to a lawyer if you think the land you improved is government-owned, as liens may not attach to some government-owned property.

If you are within the timeline for registering the lien, you must file two documents with the Land Registry:

- Claim of Lien for Registration form, and

- an Affidavit (sworn document) in support of the lien. You will need to get a lawyer, notary, or commissioner of oaths to take your affidavit before you can submit it.

The claim must include:

- a description of the work done or the services or materials provided

- amount claimed

- last day work was done and/or materials supplied

- a description of the property to be charged (exact address). If possible, get the property's Parcel Identification Number (“PID”) and include that in your description.

You should hire a lawyer to help you draft and file these documents and ensure you have included all the necessary information.

Once you finalize these two documents, contact the Land Registry. Ask them to register the documents against the property you have described in the documents. There is a fee for doing so. Once registered, the Land Registry will give you a copy of a confirmation page showing you have registered a lien against the property.

Land Registration Offices are listed in the government pages of the telephone book under Land Registration, or visit: novascotia.ca

Once registered, you must give notice of the lien to all people/companies named in your lien. Do this by sending each of them a copy of your Claim of Lien for Registration, Affidavit, and the Land Registry’s confirmation page showing that you have registered the lien. Give this notice as soon as possible, and keep a record for your files.

The lien takes effect from the date of registration and has priority over subsequent purchasers, mortgagors and other encumbrances of the land. However, prior encumbrances have priority over the lien, such as lenders that have advanced money under their mortgages before you registered the lien.

Regardless of who files their lien first, all lien claimants of the same class (all subcontractors working for a specific general contractor or all sub-subcontractors working for a specific sub-contractor) are treated equally and recover pro rata.

How long do I have to register a lien?

You have 60 days from your last day of work, or the last day you supplied materials, to register your lien at the appropriate Land Registration Office.

After 60 days, you can no longer register a lien, but you may still be able to sue the person who owes the money in either Small Claims Court or the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia for the amount they owe you.

Where do I register a lien?

You must file your lien with the Land Registration Office in the county where the property is located. There is a fee for this service. You may require a lawyer to register your lien at the Land Registration Office. Local Land Registration Offices are listed in the government pages of the telephone book under Land Registration, or visit: novascotia.ca/sns/access/land/land-registry.asp

Step 2 How to start a lien action

Once you have registered your lien and notify the property owner, the owner may pay you the lien amount or ask their general contractor to do so. They may also want to discuss settling with you for a lesser amount. They may also tell you that they do not agree with the amount you claim and/or may argue that your work was deficient; therefore, you are not entitled to payment.

No matter how the owner responds, if you do not get paid, you must file a lien action to preserve your lien. This is called ‘perfecting’ the lien. Specifically, you must file a Statement of Claim with the Nova Scotia Supreme Court within 105 calendar days of the last day of work to perfect the lien and prevent it from expiring. There is a fee for doing so.

The 105 calendar days start from the last day of work, not from the date you register your lien. Any negotiations you are in with the owner will not stall or change this deadline in any way, so be sure to keep close track of it.

The Statement of Claim must state all the facts you will rely on to prove your claim, the causes of action against the defending parties, and the damages you claim. You should hire a lawyer to help you draft and file the Statement of Claim, as there are several rules around what you must include in these documents and what is improper to include. It may be possible to claim breach of contract or other causes of action in addition to making a lien claim, which is a complicated decision that you will likely need a lawyer to help you with.

You also must draft a Certificate of Lis Pendens document. A Certificate of Lis Pendens is a document that confirms you have started a lawsuit to perfect the lien properly. You must file the Certificate of Lis Pendens with the court at the same time as filing your Statement of Claim. The court will stamp and sign the Certificate of Lis Pendens, which you must then register with the Land Registry.

You must file several copies of the Statement of Claim- one for the court, one for you, and one for each of the other parties you claim against. The court will stamp all the copies when you file them. The court will keep one copy and give you the rest.

You must then 'personally serve' these copies on each party. You must do that within 30 days of filing.

Personal service means someone must hand the document to the person. You cannot complete personal service by mailing documents to someone or using a courier, fax, or registered mail. If the person you need to serve has a lawyer, that lawyer may accept service for their client. You should check with the lawyer to make sure they will accept service of the documents. To serve a company, you have to hand the document to the Recognized Agent for the company.

You can hire a process server if you do not want to serve the parties personally. Professional process servers, also known as bailiffs, charge a fee for this service.

Step 3 Register the lien action

You must register the lien action with the Land Registry to perfect your lien. You must do this within 105 days of the last day of work. Your lien will expire if you do not register the lien action with the Land Registry.

To register your lien action with the Land Registry, you must have filed a Certificate of Lis Pendens document when you filed your claim in court. A Certificate of Lis Pendens is a document that confirms you have started a lawsuit to perfect the lien properly. You must file the Certificate of Lis Pendens with the court at the same time as filing your Statement of Claim.

I want to register a lien, but someone is telling me that I agreed I would not register one; what do I do?

The Builders' Lien Act says that unless you are a manager, officer or a foreman, a spoken or written agreement that you will not exercise your right to make a lien claim is null and void. This means you cannot relinquish your right to make a lien claim. You might voluntarily choose not to register a lien, but no one can stop you from making a lien claim by insisting that you or someone on your behalf agree beforehand not to make a claim.

What is a holdback?

The law requires owners and contractors in the construction chain to keep or ‘hold back’ 10 percent from each payment they make to contractors and sub-contractors. This percentage is known as the holdback. All the amounts held back by all of the owners and contractors in the chain form what is known as the lien fund. The lien fund is the pool of money that lien claimants can resort to if they are not paid.

The holdback must be held for 60 days after the work has been ‘substantially performed’. Work is substantially performed under the Builders' Lien Act when

(1) the work or improvement is ready for use or is being used for the purpose intended; and

(2) the work remaining under the contract can be completed at a cost of not more than two and one-half percent of the contract price.

Once these two requirements have been met, the owner/contractor must release the holdback to the contractor/supplier(s) below them in the construction chain.

If, after substantial performance, there is still some work to be done on the property to ensure that it is 100 percent completed, the owner/contractor is required to hold back 10 percent of the value of that remaining work. This “finishing holdback” must be retained until 60 days from the date of ‘total performance’ (i.e., when the project is 100 percent complete).

Subcontractors may apply for the early release of part of the holdback if they finish their work on a specific aspect of the project before the entire project is complete and they want the remaining 10 percent of their money as soon as possible. To do this, subcontractors must get the project consultant to certify that they have substantially performed the contract. If there is no consultant, then the owner and the general contractor have to jointly certify that the work has been substantially performed. 60 days after certification of substantial performance (assuming noone files a lien related to that subcontractor’s work), the owner can then reduce its project holdback by the amount of the subcontractor’s holdback and release that amount to the general contractor. The general contractor can then release that same amount to the subcontractor.

Owners must give notice that the general contractor has reached substantial performance of its contract. Specifically, owners must post a notice on the Construction Association of Nova Scotia website and at the job site in a prominent location. However, these notice requirements do not apply to property that is:

(1) owned and occupied by the owner and/or their spouse or common-law partner;

(2) for single-family residential purposes; and

(3) where the value of the work is for $75,000.00 or less.

What do holdbacks have to do with my lien claim?

An owner or contractor’s liability to sub-contractors further down the construction chain with whom they are not in a contractual relationship is capped at the holdback amount of 10 percent. Therefore, when anyone other than the general contractor makes a lien claim, the holdback limits the extent of an owner or contractor’s liability to 10 percent of the payments they have made to sub-contractors or the amount still owing to the general contractor (for example, unpaid progress payments for work performed).

Can an owner have a lien removed from their property before trial?

If the parties settle before the matter goes to trial, the lienholder must remove the lien as a condition of the settlement. However, even if the parties do not settle, the owner can still remove the lien from the property before trial.

To do so, the owner must post the amount of the lien claim plus 25 percent into court for the court to hold until the claim is decided. The money is typically posted as a lien bond from a surety company, a letter of credit or a certified cheque from a bank. This shifts the security from the property to the court. This is known as ‘vacating’ the lien and is often done by owners who want to get the lien off their property quickly so they can sell it or finance it. A court application might be necessary to vacate the lien. However, if the parties consent, the court will typically make an order without needing the parties to appear in court.

What happens if I miss a deadline or do not want to make a lien claim?

If you have missed a deadline for registering or enforcing your lien, or if you do not want to make a lien claim at all, you may be able to sue the person or company you have a direct contract with in either Small Claims Court or the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia for money that is owed to you. If you are suing for under $25,000, you should claim in Small Claims Court. This will be a regular breach of contract claim, not a lien claim. This means you will follow the normal processes of the Small Claims Court or the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. If, after you get your judgment, the person who owes you money doesn’t pay you, you would have to take steps to enforce the judgment. See Enforcing a Small Claims Court Order: A Guide for Creditors at courts.ns.ca

What is a breach of trust claim?

If you missed a deadline and you can no longer make a lien claim, you may be able to claim for a “breach of trust”. You must make a breach of trust claim in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia regardless of whether the claim is for less than or more than $25,000, as the Small Claims Court cannot deal with breach of trust claims. You will likely need a lawyer to make a breach of trust claim.

The law says that money an owner gets to fund a construction project is held “in trust” for the contractors' benefit until the owner uses it to pay the contractors. This means that even though the money is in the owners’ hands, the law trusts that the owner will hold this money for the contractors. If the owner does not pay the contractors this money, they can be said to have broken this trust agreement, and the court may find that they have committed a “breach of trust”.

Similarly, the law says money a contractor or a subcontractor gets for other subcontractors, labourers and/or suppliers is held in trust for other subcontractors, labourers and/or suppliers even though the money is in the hands of the contractor or subcontractor. If the contractor or subcontractor uses the money for their own purposes and fails to pay the subcontractors, labourers or suppliers, the court may find that they have committed a breach of trust.

Courts have said that the trustee's duty to preserve the trust fund for the benefit of workers and suppliers is ongoing and does not end until all work has been completed and all workers and suppliers have been paid. However, the trustee only owes this obligation to people directly below them in the construction pyramid. That is, the only beneficiaries of the trust are those who have a direct contract with the contractor who owes them money. The courts have said that once a contractor has paid those directly below her in the construction pyramid, she has fulfilled her trust obligations. Bringing a breach of trust claim in the Supreme Court may be particularly important if you have missed deadlines and cannot bring a lien claim anymore or if the person who owes you money might be declaring bankruptcy.

Do I need to hire a lawyer?

This can be a complicated area of law. Hiring a lawyer for advice about registering and enforcing a lien is a good idea.

A lawyer can help you:

- decide whether it is worth it for you to file a lien

- prepare your affidavit, which is a sworn statement by you attesting to the truth of your claim. The affidavit must accompany your claim form when you first register your lien

- accurately fill out and file the appropriate forms

- follow the time limits in the Builders' Lien Act

- assist you with a breach of trust claim or

- negotiate payment, possibly avoiding the time and cost of going to court.

If negotiations are unsuccessful, you will likely need a lawyer to handle the proceedings through the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. A lawyer can also advise you on whether you should go ahead and sue on your own in Small Claims Court instead of claiming a lien. You can sue in Small Claims Court for less than $25,000. However, you will not be making a lien claim. You will just be suing for money. You are allowed to represent yourself in Small Claims Court.

For property owners

Can a person register a lien if I did not hire them?

Yes. Liens are available to contractors as a remedy precisely because contractors do not have a direct contract with the property owner that would provide them with a common law remedy for breach of contract. A lien claimant may register a lien even if you did not directly hire them to work on your property. Your contractor or a subcontractor may have hired them.

For example, you hired a general contractor to build your house and have made regular payments to them. Your general contractor subcontracted an electrician to do the electrical wiring in your home but failed to pay her for the work. The unpaid electrician can register a lien against your property. Equally, if the general contractor paid the electrician but did not pay the employee who worked on the project, the electrician’s employee can register a lien against your property.

Can a person register a lien if I dispute the debt?

Yes. Sometimes, there are disagreements about the quality of work done on a property. There may be deficiencies in the work, or you might dispute the amount the contractor claims in the lien. Disputes over the quality or completeness of the work done do not interfere with a contractor’s right to register their lien against your property and file a lien claim in the Supreme Court.

After hearing from all sides, the court would decide whether the lien claim is valid and how much money is owed, if any.

How do I defend against a lien claim?

As noted above, the contractor has to register their lien with the Land Registry no more than 60 days after their last day of work on the property. From there, they must file a Statement of Claim with the Nova Scotia Supreme Court and a Certificate of Lis Pendens with the Land Registry within 105 days of the last day of work.

If you think the lien is invalid, you can defend the lien claim by filing a Notice and Statement of Defence (see How to Defend an Action) with the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. In that Defence, the owner should explain the significant facts and why they think the lien claim is invalid.

Owners (or general contractors on behalf of owners) should track what contractors are on their property and when. This may enable them to challenge the lien claim because the contractor failed to meet one of the Builders' Lien Act deadlines. One of the easiest ways to defend a lien claim is to state that the lien claimant did not register their lien within 60 days of their last work day on the project. If the owner is confident about that argument, they could file a motion to discharge the lien. Courts strictly apply the deadlines under the Builders' Lien Act.

How do I have the lien removed from my property once the claim is decided or settled?

If you settle with the contractor before they have filed a law suit (action), you may have a lien removed from your property by registering a Receipt in Discharge of Lien signed by the lien claimant with the Land Registry. However, if the contractor starts an action, you must file a Consent Dismissal Order with the court and then register a Discharge of Lien and Affidavit of Verification with the Land Registry.

If the contractor has already started a lawsuit, the court will decide whether the contractor, subcontractor, labourer, or supplier is entitled to the money they are asking for. If you want the lien removed from your property before the court decides the case, you must apply to the Supreme Court for an order to remove the lien.

An owner can also remove the lien from the property before trial without settling with the contractor. To do so, the owner must post the amount of the lien claim plus 25 percent into the Court for the Court to hold until the claim is decided. The money is typically posted as a lien bond from a surety company, a letter of credit or a certified cheque from a bank. This shifts the security from the property to the Court. This is known as ‘vacating’ the lien and is often done by owners who want to get the lien off their property quickly so they can sell it or finance it. A court application might be necessary to vacate the lien. However, if the parties consent, the court will typically make an order without needing the parties to appear.

What are my holdback obligations as an owner?

As an owner, you must hold back 10 percent of what you pay to the company or person directly below you in the construction chain during construction. This amount you are holding back is called the ‘lien fund.’ As owner, you are the fund's trustee. This is the pool of money that lien claimants can resort to if they are not paid.

The holdback requirement comes directly from the Builders' Lien Act. Failure to comply with it could mean you will pay an extra 10 percent for your project. For example, if you pay your general contractor the total amount of their contract price instead of holding back 10 percent, and if the general contractor cannot pay their sub-contractors, there is a risk that those sub-contractors will seek payment from the lien fund. If you did not keep a lien fund, you are liable up to the holdback amount to pay any sub-contractors, even though you have already paid the holdback to the general contractor. Therefore,owners must holdd back the 10 percent amount to protect themselves from this risk.

The holdback must be held for 60 days after the work has been ‘substantially performed’. Work is substantially performed under the law when

(1) the work or improvement is ready for use or is being used for the purpose intended; and

(2) when the work remaining under the contract can be completed at a cost of not more than two and one-half percent of the contract price.

Once these two requirements are met, the owner/contractor must release the holdback to the contractor/supplier(s) below them in the construction chain.

If, after substantial performance, there is still some work to be done on the property to ensure that it is 100 percent completed, the owner/contractor is required to hold back 10 percent of the value of that remaining work. This “finishing holdback” must be kept until 60 days from the date of ‘total performance’ (i.e., when the project is 100 percent complete).

Subcontractors may apply for early release of part of the holdback if they finish their work on a specific aspect of the project before the entire project is complete and they want the remaining 10 percent of their money as soon as possible. To do this, subcontractors must get the project consultant to certify that they have substantially performed the contract. If there is no consultant, the owner and the general contractor must certify that the work has been substantially performed. 60 days after certification of substantial performance, the owner can reduce its project holdback by the amount of the subcontractor’s holdback and release that amount to the general contractor. The general contractor can then release that same amount to the subcontractor.

Owners must give notice that the general contractor has achieved substantial performance in its contract. Specifically, owners must post notices on the Construction Association of Nova Scotia website and at the job site in a prominent location. However, these notice requirements do not apply to property that is:

(1) owned and occupied by the owner and/or their spouse or common-law partner;

(2) for single-family residential purposes; and

(3) where the value of the work is for $75,000.00 or less.

You should get legal advice about your particular situation.

Do I need to hire a lawyer?

This is a complicated area of law. It is a good idea to hire a lawyer for advice about defending a lien claim, which may include counter-claiming against the contractor for deficiencies that the owner had to pay to repair, negotiating with the contractor, or removing a lien from your property.

Last reviewed: June 2024

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Melanie Gillis at McInnes Cooper for reviewing this content.