We are thrilled to have partnered with Dal Legal Aid to help bring comprehensive Residential Tenancy information to folks who need it. Check out The Tenants' Rights Video Series, and information about The Tenants' Rights Guide below.

Click on a topic below to learn more.

Basics | Renters | Owners | Neighbours

Basics

10 Things Everyone Should Know About Real Property Law in NS

This page provides information about some of the most essential things Nova Scotians should know about real property law.

There are different kinds of property. This page is about “real property,” the legal term for land and the buildings attached to the land.

This is not a comprehensive guide; it’s just an introduction to some basics. It does not replace advice from a lawyer.

Understanding these ten points will help you avoid unnecessary legal disputes and handle situations involving property rights more confidently.

1. Property law is different on and off reserve

Individual band members do not “own” reserve land like people do off reserve. Reserve land belongs to the Band as a collective, and the Band Council manages it for the community.

Band Council can allocate land to band members and make by-laws about the occupation and use of reserve land. That includes making by-laws about things like:

- Construction and new development

- Occupancy

- Transfer of rights

- Trespass

- Zoning

Although people sometimes use the term “tenancy” to describe their living situation on reserve, the Residential Tenancies Program does not have jurisdiction over tenancy disputes on reserve land.

2. There are lots of different property rights

There are many different property rights. Property law textbooks talk about “bundles of rights.” Your bundle of rights might be a lot different than someone else’s.

For example, property rights can include rights related to

- Title

- Possession

- Use

- Quiet enjoyment

- Transfer

- Granting permissions or “licenses”

- Using the property as security for a loan

This isn’t a complete list; it’s just some of the most common examples.

A person might have some, none, or all of the various rights associated with a piece of property.

For example, tenants have the right to possess and use a property subject to the terms of their lease agreement, but they don’t have the right to sell it or use it as security for a loan.

People sometimes mistakenly believe that property rights are uniform and that their property rights must be identical to those of their friends or neighbours. This can give people mistaken ideas about what property rights they have and lead to disputes rooted in misunderstandings.

3. The law puts limits on property rights

In Canada, all rights are subject to limits. Property rights are no exception. Lots of different things can limit property rights. For example, they can be limited by:

- Contract terms

- Easements and restrictive covenants

- Rights of neighbours

- Band by-laws

- Municipal by-laws

- Provincial and federal laws

People sometimes mistakenly believe they have unrestricted freedom on private property. This can result in unnecessary and very avoidable conflicts with neighbours and regulators.

4. To get title, you need a proper transfer of title (and a lawyer)

Off-reserve, each parcel of land has registered title holders who are considered the owners of that parcel. The title holders are usually in control of the land and can usually transfer, sell, or mortgage it.

To get title to a parcel of land, someone with the proper legal authority must transfer some or all of a previous title holder's rights to you. For example:

- An owner might sell you their land. Contracts for land transfers must be in writing and signed by the parties. The title holder prepares a deed with the help of a lawyer, which the lawyer registers in the Land Registry System.

- An owner might give you land in their will, which would be transferred to you by the personal representative of their estate. The personal representative will need to get a Grant of Probate and transfer the land to you with the assistance of a property lawyer.

- If you're legally married and your spouse owns property, they might transfer title to you at separation as part of your divorce settlement. The settlement terms must be written in a signed agreement, and a lawyer must complete the transfer.

- You may inherit land as an heir where the deceased owner did not leave a will. An eligible person will need to get a Grant of Administration from the Probate Court and transfer the land to you with the assistance of a property lawyer.

Almost every single land transfer in Nova Scotia now requires the involvement of a property lawyer authorized to use the Land Registry System (even “private sales”). In rare cases where a lawyer isn’t required, involving a lawyer is still a good idea because a lot can go wrong without one.

Sometimes, people mistakenly assume they can complete a real estate transaction informally without a lawyer or written agreement. In some cases, people may be misled into believing that ownership has been transferred even though it hasn’t because the proper legal steps were never taken. Misunderstandings about property ownership and title can lead to conflicts, many involving family members.

5. Squatter’s rights are hard to get

You do not get squatter’s rights just because you occupy a property you don’t own. It takes a long time before a person might acquire squatters' rights. It takes at least 20 years on private property and 40 years on government property. The time is just one requirement. There are lots of other conditions that apply.

People frequently misuse this term. It’s often used in scenarios where it’s not applicable—such as occupancy situations where the so-called "squatter" actually had the landowner's permission to be there.

6. Not everyone with a claim against a property owner can register a lien

A lien is a type of secured interest in a property. A lien holder doesn’t own the property. A lien holder is someone the property owner owes money to; their lien corresponds to a financial obligation on the part of the property holder.

Not everyone with a financial claim against a property owner can register a lien. The lien must be legally authorized by the terms of a contract, statute, or by a judge in a court order. For example:

- Mortgages are contracts that give the lender the right to register a lien against the property subject to the mortgage.

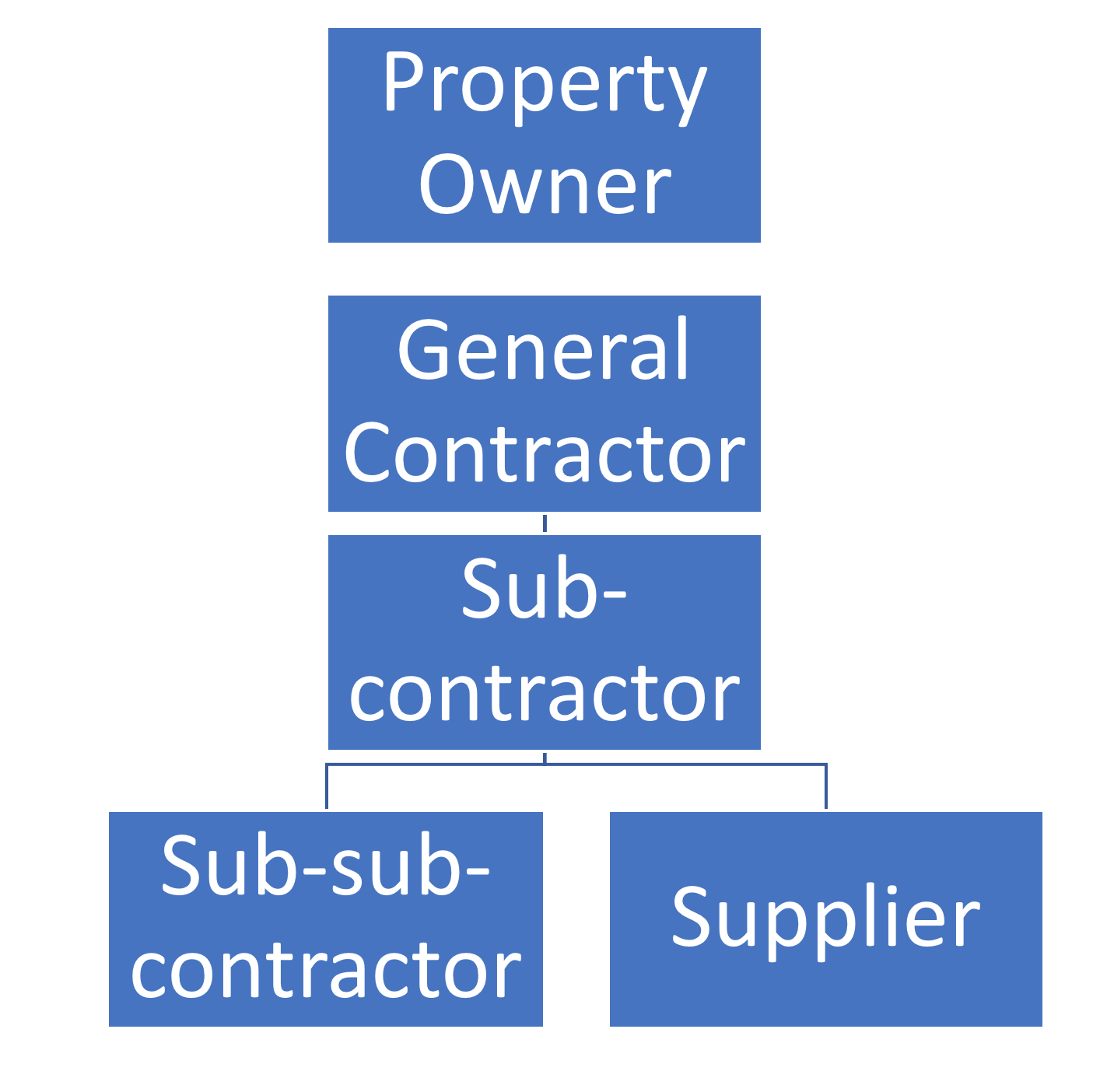

- The Builders’ Lien Act allows contractors to register liens against property they have worked on.

- A person who successfully sues a property owner in court can register the judgment, which creates a lien against the property.

People sometimes threaten to "put a lien" on a property owner, even when it’s not a realistic option. This happens because people either misunderstand when a lien is possible or deliberately misuse the term as a scare tactic.

7. Small Claims Court can’t hear disputes about land ownership

If there’s a dispute about who owns a piece of land that the parties can’t resolve, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court has jurisdiction (unless the land is on reserve). The parties cannot use the Nova Scotia Small Claims Court.

This means land ownership disputes can be expensive. Attempting to resolve an ownership dispute without assistance from a property lawyer is not recommended.

8. If you’re paying rent, you’re probably a tenant

A tenant is a person who pays rent to occupy the place they live. Rent means money or anything else of value that a person pays in exchange for the right to occupy their place.

Landlords and tenants are supposed to use a standard form of written lease called a Form P. However, you can be in a tenancy even if you don’t have a written lease.

If you live on property you don’t own and are paying money to live there; you’re probably a tenant unless one of these exceptions applies. Being a tenant means that a law called the Residential Tenancies Act applies to you and your landlord. That means some rules apply, including rules about how your tenancy can end.

If you’re uncertain whether you’re in a tenancy, you can contact the Residential Tenancies Program to discuss your situation with a staff person there.

The Residential Tenancies Program is usually just called Residential Tenancies. It is the branch of the provincial government that enforces the Residential Tenancies Act and deals with disputes between landlords and tenants. It is a program of Service Nova Scotia.

You can contact Residential Tenancies by attending your nearest Access Nova Scotia location or by calling 1-800-670-4357 and following the prompts.

9. Not all occupants are tenants

Not everyone who occupies a property they don’t own is a tenant. To be a tenant, you must either be listed as a tenant under the terms of a lease or pay rent.

Occupants do not have the same rights as tenants. What rights an occupant has depends on the circumstances related to their occupancy.

There are lots of different occupancy scenarios; here are just a few:

- Couch surfing (living rent-free with a family member or friend)

- Living on estate property (property owned by a deceased person)

- Living in an outbuilding on someone’s land (like a garage, bunky, laneway house, or shed)

- Parking an RV or other vehicle on someone’s land.

If you’re unsure whether you're a tenant or an occupant, you can contact the Residential Tenancies Program to discuss your situation with a staff member. You can contact Residential Tenancies by attending your nearest Access Nova Scotia location or by calling 1-800-670-4357 and following the prompts.

10. Disputes between landlords and tenants go to Residential Tenancies

Landlords and tenants sometimes fantasize about suing each other. That rarely makes financial sense.

If you’re a landlord or a tenant with a dispute about your tenancy that you can’t resolve, the dispute goes to Residential Tenancies, not civil court.

The Residential Tenancies Program does many things, but one of its main roles is to act as an administrative tribunal for landlord-tenant disputes. That means it has the legal authority to hear most disputes between landlords and tenants.

Here is more information about the Residential Tenancies dispute resolution process.

Last Reviewed: June 2024

Giving and Getting Property Rights in NS

There are different kinds of property. This page is about “real property,” the legal term for land and the buildings attached to the land.

Property rights are the legal rights that a person has over a property. There are lots of different property rights, including rights related to things like:

- Possession and use of the property

- Quiet enjoyment

- Title and the ability to transfer ownership

- Granting permissions or “licenses” to use the property

- Using the property as security for a loan

A person might have some, none, or all of the various rights associated with a piece of property.

For example, tenants have the right to possess and use a property subject to the terms of their lease agreement, but they don’t have the right to sell it or use it as security for a loan.

Canadian property law depends on rights transfers. To get property rights, someone must transfer some or all of their property rights to you. There are a couple of exceptions, but they’re not common.

This page explains how some of the most common property rights are transferred in Nova Scotia. Specifically, this page has information about:

- Transferring ownership of property (transferring title)

- Creating a tenancy

- Becoming an occupant

These things are important because they directly affect how secure your housing situation is.

This page provides general information about the law. It does not replace advice from a lawyer.

The information on this page applies off-reserve. It does not apply to reserve land.

Transferring title to property

Off-reserve, each parcel of land has registered title holders who are considered the owners of that parcel. The title holders usually control the land and can transfer, sell or mortgage it.

The most common ways that people get title to property are:

- Purchasing the property from the owner(s)

- Receiving the property as a gift (from a person who is still alive)

- Receiving the property as a bequest from a deceased person's estate (basically a gift from someone who has died).

Buying and selling land

The most common way that people transfer title to land is by sale.

There is a well-established process for buying and selling land in Nova Scotia. A written Agreement of Purchase and Sale is required. An Agreement of Purchase and Sale is a formal offer made by the buyer to the seller to buy the property mentioned in the agreement. A seller can accept, reject, counteroffer, or not respond to the Agreement of Purchase and Sale.

The agreement must be in writing and signed by the parties. If you use a realtor, your realtor will use the standard form endorsed by the Nova Scotia Real Estate Commission.

Do not sign an Agreement of Purchase and Sale without consulting a property lawyer first.

When the sale is complete, the title holder(s) prepares a deed with the help of a lawyer, which the purchaser’s lawyer registers in the Land Registry System. Once the deed is registered in the Land Registry Office, the purchaser becomes the property's title holder and gets property rights.

Here is more detailed information about:

Land given as a gift (while the owner is still alive)

Sometimes, people decide to give land as a gift. When people want to give land as a gift, they’re often surprised that there are costs involved, and there can be tax implications as well.

Transferring land as a gift is basically the same as transferring land via sale; it’s just that the terms of the underlying agreement are different. With a gift there’s no money exchanged, so an Agreement of Purchase and Sale is not required. However, the transaction still needs to be properly documented. The gift giver must sign a deed confirming the transfer of title.

If you want to give property as a gift

If you want to give someone land as a gift, consult with a property lawyer so that they can advise you about the tax consequences and the best way to give the gift based on your circumstances.

Because the process for gifting land is basically the same as selling it, the cost of a lawyer is similar whether you’re selling your land or giving it away.

In Nova Scotia, land given as a gift is not subject to deed transfer tax. However, if the property you’re giving away is not your principal residence, capital gains tax will apply even if you give the land away for free. That’s because even if you give your land away, the Canada Revenue Agency deems the transfer a sale at fair market value.

If the person you plan to give the property to won’t be living in the property as their principal residence, there will be capital gains tax implications for them in the future if they decide to sell it.

If someone wants to give you property as a gift

Promising land as a gift is not worth much if the proper actions do not follow it up. The intention to give something as a gift is usually insufficient to protect the receiver. The gift needs to be completed by the gift giver before the receiver can take any benefit from it.

If someone says they want to give you land as a gift, say thank you, confirm that they’re serious, and politely ask them to consult with a property lawyer so they can put that in writing for you.

Don’t assume the land is yours just because they said they want to give it to you. Until you see legal documentation like a signed gift agreement, a deed, a will, or the terms of a trust, the gift is just an idea.

Land left in a Will

When someone makes a Will, they usually appoint a person to act as the personal representative of their estate. That person is called the executor. Part of their role is to deal with the estate assets according to the instructions in the Will.

When a landowner leaves someone their land in their Will, probate is required. Probate is the legal process of validating and administering the Will or appointing an administrator if there is no Will.

The personal representative of the estate will need to obtain a Grant of Probate before they can transfer title to the land. A Grant of Probate is a legal document that confirms the validity of the deceased person's Will and gives the executor the authority to manage and distribute the estate.

After the personal representative gets the Grant of Probate, there is a six-month advertising period during which the personal representative is not supposed to transfer the land (or any other estate assets).

The estate must pay some capital gains tax (even if the land was the deceased's principal residence). Capital gains accrue to the estate from death until the land is transferred to the beneficiary. The personal representative of the estate will need to use estate assets to pay any taxes owed.

Unless the Will says otherwise, the personal representative is responsible for the land until they transfer it. That means the presumption is that they are responsible for things like:

- maintaining the property

- paying the mortgage (if applicable)

- paying property taxes

- making decisions about land use (including decisions about occupancy).

The beneficiary does not always receive the land. It depends on the financial situation of the estate as a whole. For example, the beneficiary may not receive the property if:

- the deceased person was insolvent,

- a lender was foreclosing on the property, or

- the deceased mortgaged the property on terms that the estate or the beneficiary can’t handle.

If you plan to leave someone land in your Will, consult with a wills and estates lawyer for estate planning advice.

What happens to land when there is no Will

When a landowner dies without a Willl, probate is required to administer the estate. If you die without a valid Will, someone must manage your estate. This person must apply to the Probate Court to be appointed as the administrator of the estate.

The administrator is usually a close family member or someone else with an interest in the estate. Nova Scotia law prioritizes family members, such as spouses, children, or relatives. It may not necessarily be someone you would have chosen. If there’s no one appropriate or willing to take on the role, the court may appoint a third party.

The appointed administrator will be responsible for handling the estate, including managing assets, paying debts, and distributing the remaining property.

They will be required to secure a bond as a form of insurance. In Nova Scotia, the bond is typically 1.5 times the estate's value. It ensures the administrator acts in good faith and appropriately manages the estate.

After the personal representative gets the Grant of Administration from Probate Court, there is a six-month advertising period during which the personal representative is not supposed to transfer the land (or any of the other estate assets).

The estate will have to pay some capital gains tax (even if the land was the deceased's principal residence). Capital gains accrue to the estate from the date of death until the date that the land is transferred to the beneficiary. The personal representative of the estate will need to use estate assets to pay any taxes owed.

The personal representative is responsible for the land until they transfer it. That means they are responsible for things like:

- maintaining the property

- paying the mortgage (if applicable)

- paying property taxes

- making decisions about land use (including decisions about occupancy).

Who gets the land?

When someone dies without a will, that is called dying intestate. Nova Scotia has a law called the Intestate Succession Act, which states who the beneficiaries are if a person dies without a will.

The intestate law also applies if you do not deal with all your property in your will, either intentionally or unintentionally. In this case, you are said to die partially intestate. The part of your estate not covered in your will is distributed according to the Intestate Succession Act.

Under the Intestate Succession Act the administrator of your estate distributes your property to the people considered to be your nearest relatives under the Act. The rules are not flexible. The distribution may be different from what you would want.

The basic rules are:

- If you are survived by your legally married spouse and have no children, all your property goes to your spouse

- If your legally married spouse survives you and you have one child, the first $50,000 goes to your spouse. The rest is equally divided between your spouse and child.

- If your legally married spouse survives you and more than one child, the first $50,000 goes to your spouse. One-third of the rest would go to your spouse, and two-thirds to your children.

- If you are survived by your children but no legally married spouse, your whole estate would go to your children, each getting an equal share.

- If you had no legally married spouse or children, your whole estate would go to your nearest relatives by blood or adoption, by order of priority as listed in the Intestate Succession Act. Relatives by marriage are not included.

A surviving legally married spouse will always get up to $50,000 from the estate before anyone else. If your surviving legally married spouse is not a joint owner of the family home, they may choose to take the home and household contents instead of, or as part of, the $50,000.

No protection for common-law partners, stepchildren, or grandchildren

The Intestate Succession Act does not protect common-law partners, stepchildren, or grandchildren. So, it is essential to make a will if you want your common-law partner, stepchildren, or grandchildren to inherit something from your estate when you die.

Here’s why:

- If you die without a will, only your surviving married spouse or registered domestic partner can inherit. Common law partners are not included as a 'spouse' under the Intestate Succession Act. Your common-law partner will not automatically inherit your property or money that is only in your name. Your common-law partner may have to go to court to make a claim on your estate, and may not be successful.

- If you die without a will, only your biological and adopted children can inherit. Stepchildren are not included. They would have to go to court to make a claim on your estate, and they may not be successful.

- If you die without a will, your grandchildren will only inherit from your estate if their parent (your child) died before you.

Making a Will is important

If you die without a will, there will be extra steps in the process of settling your estate, which will mean additional costs and delays. This may add to your family’s pain and distress. It will also mean that there will be less left to distribute.

Also, family members may disagree and argue about how you intended to distribute your property.

Here is more information about making a will.

Land placed in a trust

Another way that people sometimes transfer their land is by creating a trust.

A trust is a legal arrangement where the property owner (the settlor) transfers property (such as land) to a trustee, who holds and manages the property on behalf of one or more beneficiaries according to the terms set out in the trust document.

In a trust, the trustee holds the legal title to the property (so the property is in the trustee’s name), but the benefits of the property, like any income or rent, go to the beneficiary.

To transfer land by trust

You must consult a lawyer, who will advise you on the pros and cons of using a trust.

If you decide to proceed, the lawyer will create a trust agreement. This document outlines the terms of the trust, including who will manage the property (the "trustee") and who will benefit from it (the "beneficiaries").

The property owner will have to transfer the land to the Trust. The settlor officially transfers land ownership into the trust by changing the property title to reflect that the trustee now holds the land on behalf of the beneficiaries. The settlor no longer owns the land directly but has given control to the trustee.

The trustee manages the land and is responsible for managing the property according to the terms of the trust. This could involve deciding how the property is used, rented, or sold. The trustee must act in the best interests of the beneficiaries.

Transfer to beneficiaries. When the time comes, the trustee will transfer the property to the beneficiaries according to the terms of the trust. Depending on how the trust is set up, this could happen during the settlor’s lifetime or after their death.

Different types of trusts can be created for the transfer of land:

- Inter Vivos Trust (Living Trust): This type of trust is created during the settlor's lifetime. The settlor transfers land to the trust while they are alive. The trustee then manages the property for the benefit of the beneficiaries. Intervivos trusts can be revocable or irrevocable, depending on whether the settlor retains control over the trust and its assets.

- Testamentary Trust: This type of trust is created by a Will and only comes into effect upon the settlor's death. If the settlor’s Will specifies that certain property, such as land, is to be held in trust for beneficiaries after their death, a testamentary trust is established. This trust cannot be altered after the settlor’s death.

Trusts require careful planning

Trusts can be helpful for several reasons, such as avoiding probate, managing property for minor children, or controlling how property is passed on to beneficiaries. They're also a way to ensure the property is managed according to the settlor’s wishes.

However, they involve legal complexities, tax consequences, and ongoing responsibilities for the trustee. Careful estate planning is required. For these reasons, it is important to consult a lawyer with experience in estate planning and trusts to ensure the trust is set up correctly and serves the settlor’s goals.

Forming a residential tenancy

A residential tenancy is an agreement in which the landlord gives the tenant certain property rights in exchange for rent payments.

The rights of both sides are protected by the terms of their lease agreement and by a law called the Residential Tenancies Act.

Two ways to form a tenancy agreement

There are two ways to form a tenancy agreement:

- By signing a lease, which is supposed to be in the standard form called a Form P.

- By paying rent in exchange for a place to live.

Important: Since a tenancy can be formed by one person paying rent in exchange for a place to live, that means it’s possible to form a tenancy even if the people involved:

- Did not sign a lease,

- Did not intend to form a tenancy,

- Do not call themselves “landlord” and “tenant”.

The bottom line is that if someone pays rent to live somewhere long-term, they’re probably a tenant (unless one of the following exceptions applies).

The exceptions - when a person paying rent isn’t a tenant

People staying in the following places are not considered tenants, even if they’re paying to be there:

- Hospitals, including psychiatric hospitals and maternity hospitals

- Jails, prisons or reformatories

- Licensed maternity homes

- Nursing homes

- Residential care facilities

- Universities, colleges, and other learning institutions.

Occupants of those places have rights, too, but they are not tenants, and they are not covered by the Residential Tenancies Act.

When there’s no written lease

Landlords and tenants are supposed to use a standard form of written lease called a Form P. However, you can be in a tenancy even if you don’t have a written lease.

If you live on property you don’t own and are paying rent to live there; the Residential Tenancies Program can deem you a tenant even if you don’t have a written lease.

When that happens, they deem the parties to be in a periodic, month-to-month lease with an anniversary date corresponding to when the tenant first moved in.

Being a tenant means that the Residential Tenancies Act applies to you and your landlord. Rules apply, including about how your tenancy can end.

If you’re not sure whether you’re in a tenancy

If you’re uncertain whether you’re in a tenancy, you can contact the Residential Tenancies Program to discuss your situation with a staff person there.

The Residential Tenancies Program is usually just called Residential Tenancies. It is the branch of the provincial government that enforces the Residential Tenancies Act and deals with disputes between landlords and tenants. It is a program of Service Nova Scotia.

You can contact Residential Tenancies by attending your nearest Access Nova Scotia location or by calling 1-800-670-4357 and following the prompts.

Becoming an occupant

Occupant is a broad term with different definitions depending on the context.

On this page, we use the word “occupant” to refer to a person who is not a tenant but who lives on residential premises owned by another person.

There are lots of different scenarios involving occupants. For example:

- A homeowner who invites their new partner to live with them.

- A person who parks their RV on their friend's property.

- A homeowner who invites their elderly mother to move into a spare bedroom.

- An adult child who moves in with their elderly parents to provide home care.

What these scenarios have in common is that the occupant has permission from the appropriate person.

How to become an occupant

To become a lawful occupant, you need permission from the owner or the person legally authorized to make occupancy decisions. If you occupy a property without permission from the appropriate person, they can take steps to remove you from the property.

Usually, the property owner gets to make decisions about occupancy. However, there are some situations where a different person might make those decisions. For example:

- The owner may have delegated their authority to an attorney in a power of attorney document.

- The owner may have died, and the personal representative of their estate may have the authority to make occupancy decisions while dealing with property for the estate.

- The owner may use the services of a property management company with the authority to make occupancy decisions.

If you are permitted to occupy a property, it’s best if that permission is in writing.

If you are moving into a rental property as an occupant, ask to see the lease to confirm that you are listed as such.

Adding an occupant to your lease

Before you sign your lease

When looking for a place to rent, you should be honest with your landlord about how many people will occupy the property. Your landlord is allowed to screen all prospective occupants. If the other occupants are adults, your landlord may want to list them as co-tenants on the lease.

When you sign your lease, it should be in the standard form (Form P). The landlord and tenant(s) are listed in section 1. All other occupants are listed in section 2. Make sure those sections are accurate before you sign your lease.

After you sign your lease

If you’ve already signed a lease and want to add occupants to the lease, you need to ask permission from your landlord. If your landlord denies your request, they need to have reasonable grounds.

The Residential Tenancies Act does not give the tenants the right to add occupants. It’s up to your landlord whether to allow another occupant. However, if you request to add an occupant, your landlord can only deny the request if they have a reasonable basis.

Sometimes, your landlord may only consent to add an occupant if you sign a new lease with increased rent. In that scenario, they are not restricted by the 5% rent increase cap.

If you and your landlord cannot agree about adding an occupant, either one of you can apply to the Residential Tenancies Program for dispute resolution.

Being an occupant is less secure than being an owner or tenant

Becoming an occupant of a property does not automatically give you all of the property rights associated with that property. Occupants have far fewer rights than owners or tenants.

The rights of an occupant depend on the scenario. Often, the occupant only has the rights the owner expressly granted them.

The Residential Tenancies Act does not have specific rules or procedures for evicting occupants. Sometimes, it is far easier for owners or landlords to remove occupants than tenants.

If you are moving into a rental property as an occupant, ask to see a copy of the lease to confirm that you are listed as such.

If you are moving into a property that isn’t rented, consider putting the terms of your arrangement in writing so that everyone is clear on what rights you do (or don’t) have.

More Information

Where can I get more information?

In the housing section of our site, you can find more information about topics like:

- Buying and selling land

- Land registration and title

- The advantages of forming a residential tenancy

- Moving in with someone

For information about residential tenancies, we suggest:

- The Residential Tenancies Program website

- Dalhousie Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide

Last Reviewed: March 2025

This content was made possible by financial support from the Department of Justice Canada’s Justice Partnership and Innovation Program.

Moving in with Someone

This page provides basic legal information about moving in with someone. It applies to many different situations, including moving in with a roommate, family member, friend, or romantic partner.

Whatever the details of your situation are, there are some common legal considerations when sharing your living space with another person.

This page provides legal information only. It does not replace advice from a lawyer.

What you should know

The difference between an occupant and a tenant

Both tenant and occupant are individuals who live in or use a property, but there are key differences.

A tenant is an individual who has a lease agreement with the landlord (written or oral) and pays rent. Tenants have specific rights and responsibilities protected by the Residential Tenancies Act (RTA).

Occupant is a broad term with different definitions depending on the context.

On this page, “occupant” refers to a person who is not a tenant but who lives on residential premises owned by another person. An occupant resides on the property but doesn’t pay rent. Occupants might live in the property long-term (for example, family members or friends) or stay temporarily (for example, a visiting guest).

If the property is a rental, the landlord must consent to the occupancy. The occupant should be listed in the lease agreement unless it is a short-term arrangement (for example, a family member or friend visiting you briefly).

Although occupants are not tenants, when an occupant moves in with the landlord’s consent, they get some protection from the Residential Tenancies Act.

The Residential Tenancies Act does not apply to occupants when they move in without the landlord’s consent.

Here is more information about occupants.

You only get tenants’ rights if you have a lease agreement

Moving in with someone doesn’t automatically make you a tenant. To become a tenant, you must have a written or verbal lease agreement.

This is important because:

1) You don’t automatically get security of tenure just because you have moved in with someone.

Security of tenure refers to the right of a tenant to stay in the property they are renting.

A landlord can only evict tenants with security of tenure for a valid legal reason. In Nova Scotia, only tenants with periodic leases (month-to-month, year-to-year) have full security of tenure.

2) You can form a tenancy without signing a written lease.

For more information about forming a tenancy, see:

- Forming a Residential Tenancy

- Advantages of a Residential Tenancy

- Dalhousie Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide

- Residential Tenancies Program Renting Guide

It’s possible to form a tenancy without signing a lease

The Residential Tenancies Program can deem you to be a tenant if you pay rent as part of your living arrangement.

Landlords and tenants are supposed to use a standard form of written lease called a Form P. However, you can become a tenant even if you don’t have a written lease. That’s because a tenancy can be formed by an occupant paying money to the property owner.

Here are some key points to understand

- You don’t automatically become a tenant when you move in with someone. Not all occupants are tenants. A tenant is an individual who has a lease agreement with the landlord (written or oral) and pays rent.

- You can unintentionally form a tenancy by making rent payments. That means it’s possible to form a tenancy even if the people involved didn't sign a lease, didn’t intend to form a tenancy, and don’t call themselves “landlord” and “tenant”.

- Tenants have more legal protection than occupants. The Residential Tenancies Act (RTA) protects tenants’ rights in Nova Scotia. Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide has detailed information about tenants' rights.

If you’re only an occupant, your housing may be insecure

Often, occupants don’t realize that their housing situation is insecure compared to tenants or property owners.

Becoming an occupant of a property does not automatically give you all of the property rights associated with that property. Occupants have far fewer rights than owners or tenants.

In rental properties: Permission from the landlord is key. The landlord must approve the occupancy. If you move into a rental property without permission from the landlord, you can be removed from the property on short notice, and there can also be serious consequences for the tenant(s).

If the property is not a rental: Usually, the person who permitted the occupant to move in can revoke their permission at any time. As an occupant, you usually only have the rights the owner chooses to give to you.

Since occupants don’t have tenants’ rights, they don’t have the same protection from eviction as tenants. The Residential Tenancies Act does not have specific rules or procedures about evicting occupants. Sometimes, it’s far easier for owners or landlords to remove occupants than tenants.

Squatter's rights don’t apply

People often use the term “squatter's rights” when it doesn’t apply. Squatter's rights do not apply when you move in with someone.

When you move in with a person, you do so with that person’s consent. You cannot get squatter's rights on a property when you are living in it with the owner's consent.

Furthermore, squatter's rights claims require the claimant to show occupation of the property for 20 years; a few weeks, months, or even years is not enough to establish adverse possession.

Also, if the person you are moving in with is a tenant, you can never establish squatter's rights against a tenant.

Romantic partners

If you are moving in with a romantic partner, there are a few things you need to understand about the law.

The Residential Tenancies Program is less likely to deem you a tenant. Even if you regularly contribute to the carrying costs of your partner’s property, the Residential Tenancies Program is less likely to deem you a tenant when you’re in a romantic relationship with the property owner. That means you probably won’t have the option of using the Residential Tenancies Program dispute resolution process. Any dispute between you and your partner would go to civil court.

You don’t automatically share each other’s property and debts. Sharing a living space doesn’t mean that you share everything. You do not become liable for your partner’s debts when you move in with them. You also don’t get a share in their property or other assets. It’s up to the two of you to decide how integrated your finances will become.

You don’t automatically become a common-law couple when you move in together. The definition of common-law spouses is context-dependent. To become common-law spouses for the purposes of NS family law, you either need to:

- Live together for 2 years

- Have a child together

- Register as a domestic partnership with Vital Statistics (consult a lawyer first)

Here is detailed information about common-law relationships.

If you’re not common-law, any legal dispute about your break up would be limited in size. Each case is unique, but in the context of a short-term cohabitation with no kids, the legal disputes are usually about:

- Your contributions to the carrying costs of the property (mortgage, property taxes, utilities).

- Your contributions to purchases made during the relationship, especially costly items like cars, appliances or big pieces of furniture.

- Pets acquired during the relationship.

The claims would be limited by the duration of the relationship and the size of your contributions.

Intimate partner violence. Violence can happen at any stage in any relationship. There are lots of factors that determine how vulnerable you are. Generally, the risk of intimate partner violence goes up when you move in with your partner (and officially move out of wherever you were living previously). Intimate partner violence can take different forms in the early stages of a relationship, as your partner may threaten to remove you from their home on short notice. The best way to protect yourself from threats like that is:

- Sign a cohabitation agreement with terms about notice to quit and compensation instead of notice.

- If your partner is a tenant, ensure the landlord approves of you moving in and that you are added to the lease as a tenant or occupant.

You can sign a cohabitation agreement at any time. People sometimes mistakenly assume that only common-law spouses can sign cohabitation agreements. You can sign a cohabitation agreement at any point before or during your period of cohabitation.

Agreements are always an option

When planning to move in with someone, it's always possible to use a written agreement to record the terms of your arrangement.

What type of agreement you should have depends on the circumstances.

If you will be a tenant, you will sign a lease agreement in the standard form (Form P). Form P is a pre-written contract that complies with Nova Scotia's Residential Tenancies Act and covers all the essential parts of a tenancy.

Check out Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide or the Residential Tenancies Program’s Renting Guide for more general information about leases and residential tenancies.

So, a lease is essential if you’re in a landlord-tenant relationship. Depending on the circumstances, other agreements may be appropriate, such as:

Agreement Options for Tenants

Sublet agreements: A sublet is when a tenant rents out their space to another person with permission from the landlord. It is also known as a sub-tenancy. A sublet agreement applies between the tenant and their subletter. It’s a tenancy within a tenancy. It can have similar terms as a standard form of lease. Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide has more information about subletting.

Lease assignments: A lease assignment occurs when a tenant, with permission from the landlord, signs over their rights and responsibilities under a lease to a new person. The lease continues with the new person as the tenant. A lease assignment applies between the tenant, the assignee, and the landlord. Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide has more information about lease assignments.

Roommate agreements: Disagreements between roommates do not get heard at Residential Tenantices. A roommate agreement is a side agreement made by co-tenants in a residential tenancy. They can be used to formally record cost-sharing arrangements, such as sharing payments for rent or utilities in a particular way. Roommate agreements apply between the tenants; they do not apply to the landlord. They are enforced in Small Claims Court, not through the Residential Tenancies Program.

Agreement Options for Homeowners

Guest agreements: A guest agreement is an option if a homeowner allows someone to move in with them for free as a house guest. However, a guest agreement is inappropriate if the person is not staying for free; you should sign a lease instead. See giving shelter to a family member or friend for more information.

Cohabitation agreements: A cohabitation agreement is for people in a romantic relationship who decide to start living together. They are most commonly used when one or more of the partners owns property. They usually specify how carrying costs will be dealt with during the period of cohabitation and what rights each partner will or won’t have to the property if they separate.

Purchase and sale agreements: A written and signed agreement of purchase and sale is required to transfer property in Nova Scotia. If people are moving in together and the plan is for one of them to buy a share of the other’s property, a written and signed purchase and sale agreement is required. Consult a property lawyer before signing the agreement. Buying property is a big decision, so you should inform yourself about the process. Here is more information about buying property in Nova Scotia.

Having a written agreement can help avoid future conflicts by clearly outlining the details of the arrangement, as well as the rights and duties of all parties involved.

Common sources of dispute

Things people sometimes get into legal arguments about

When you move in with someone, disputes are possible. Knowing common sources of dispute is an important part of preventing disputes from arising.

Some of the most common sources of dispute when people start living together include disputes about:

Permission to move in: Disputes over permission to move in may arise when the person moving in does not have authorization from the appropriate person. Depending on the situation that could be the landlord, homeowner, or a person authorized to make decisions about occupancy on behalf of the landlord or homeowner.

Tenant or Occupant Status: This dispute arises when there's confusion about whether the individual moving in is considered a tenant (with rights and protections under the Residential Tenancy Act) or simply an occupant (without such rights). This is especially common when no formal lease agreement is signed. The distinction can affect eviction processes, responsibilities for repairs, and more.

Privacy Concerns: Disputes related to privacy may arise if either person feels the other has violated their privacy. This can include issues such as unauthorized entry into their personal space, sharing personal information without consent, general invasions of personal space, video surveillance, or other actions that make the individual feel their privacy is compromised.

House Rules: Conflicts can arise when the individual disagrees with or fails to follow established house rules. These rules can cover many issues, from quiet hours and cleanliness standards to using shared spaces.

Guests: Disputes regarding guests can occur if there are disagreements about how many guests are allowed, how long they can stay, or their behaviour. The presence and actions of guests can sometimes lead to tension between the individual and the landlord or other occupants.

Property Damage: Disputes may arise regarding who is responsible for maintaining and repairing the property.

Some other sources of dispute are less common but still very important to be aware of. That includes disputes about:

Crises: While less common, crisis situations can occur. These can include personal crises such as mental health crises, criminal activities, and abuse or threats of violence from a person sharing the property. It can also include natural disasters (such as fires, floods, or hurricanes) that make the property uninhabitable.

Equity in the Property: Disputes concerning equity in the property can emerge when an individual has lived in the space for an extended period without a formal lease or agreement and has contributed to carrying costs, repairs, maintenance, or improvements to the property. The person may believe their financial or labour contributions have granted them a share of the property’s value. They may claim that they have developed equity in the property. In some cases, they may assert an unjust enrichment claim, arguing that the landlord or property owner has benefited unfairly from their contributions.

In the next section, there are some tips that may help prevent some of these disputes.

Tips

Ask for basic information before you decide to move in

Here are some basic questions that you should have answers to before you decide to move in with someone.

If you are moving into a rental property:

1. Who is the landlord?

2. Are you dealing with the landlord directly?

3. If not, what is the relationship between the person you're dealing with and the landlord?

4. Does the landlord know that you might be moving in?

5. Will you sign a lease, lease assignment, or sublet agreement? If not, why not?

6. What are the terms of your lease? Is the lease periodic or fixed-term?

If you are moving in with a property owner:

1. Who owns the property?

2. If the property is co-owned, do all the owners know you will be moving in?

3. Will you be paying any money during your stay? (If so, you should be signing a lease or, if you are romantic partners, a cohabitation agreement.)

4. If you're not signing a lease:

- Why are you not signing a lease?

- Is the other person willing to document the terms of your occupancy in writing some other way? (For example, by signing a guest agreement.)

Put your agreement in writing

It is usually best to record the terms of your arrangement in writing. A well-written agreement can help avoid disputes. It also makes it easier for third parties to understand your situation.

What type of agreement you should have depends on the circumstances.

If you will be a tenant, you will sign a lease agreement in the standard form (Form P). That is a pre-written contract that complies with Nova Scotia's Residential Tenancies Act and covers all the essential parts of a tenancy. For more information, check out Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide or the Residential Tenancies Program’s Renting Guide.

Depending on the circumstances, other agreements may be appropriate, such as:

Agreement Options for Tenants

Sublet agreements: A sublet is when a tenant rents out their space to another person with permission from the landlord. It is also known as a sub-tenancy. A sublet agreement applies between the tenant and their subletter. It’s a tenancy within a tenancy. It can have similar terms as a standard form of lease. Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide has more information about subletting.

Lease assignments: A lease assignment occurs when a tenant, with permission from the landlord, signs over their rights and responsibilities under a lease to a new person. The lease continues with the new person as the tenant. A lease assignment applies between the tenant, the assignee, and the landlord. Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide has more information about lease assignments.

Roommate agreements: A roommate agreement is a side agreement made by co-tenants in a residential tenancy. They can be used to formally record cost-sharing arrangements, such as sharing payments for rent or utilities in a particular way. Roommate agreements apply between the tenants; they do not apply to the landlord. They are enforced in Small Claims Court, not through the Residential Tenancies Program.

Agreement Options for Homeowners

Guest agreements: A guest agreement is an option if a homeowner allows someone to move in with them for free as a house guest. However, a guest agreement is inappropriate if the person is not staying for free; you should sign a lease instead. See giving shelter to a family member or friend for more information.

Cohabitation agreements: A cohabitation agreement is for people in a romantic relationship who decide to start living together. They are most commonly used when one of the partners owns property. They usually specify how carrying costs will be dealt with during the period of cohabitation and what rights each partner will or won’t have to the property if they separate.

Purchase and sale agreements: A written and signed agreement of purchase and sale is required to transfer property in Nova Scotia. If people are moving in together and the plan is for one of them to buy a share of the other’s property, a written and signed purchase and sale agreement is required. Consult a property lawyer before signing the agreement. Buying property is a big decision, so you should inform yourself about the process. Here is more information about buying property in Nova Scotia.

Keep records of any payments that you make

Whatever the terms of your arrangement, you should have written records of any payments you make related to your occupancy.

That’s especially true if you make regular payments for carrying costs like rent, mortgage, utilities, or property taxes.

If you pay for something in a way that doesn’t generate a written record, you should make one of your own. For example, if you give the other person cash to make a rent payment, you can confirm that with a short email message.

Build and maintain positive relationships

Building and maintaining a positive relationship with the person you are moving in with is essential. Building and maintaining such relationships can make living together a pleasant experience for everyone involved.

Here are some tips to help with that:

Be clear and open with communication: Talk about your expectations, schedules, and any issues that arise early on. This helps to avoid misunderstandings and keeps everyone on the same page.

Respect people’s space and schedule: Give your roommate personal space and privacy when needed. Being mindful of their schedule and personal boundaries can create a harmonious living environment.

Share household chores fairly: Divide household tasks fairly and consistently follow the agreed-upon schedule. This ensures that everyone contributes to maintaining a clean and organized living space.

Be considerate of noise levels: When making noise, be mindful of your roommate's sleep patterns and study times. Using headphones or keeping the volume low can go a long way toward maintaining peace.

Maintain cleanliness: Don't leave messes behind, clear your dishes after meals, and tidy up your belongings. A clean living space is essential for everyone's comfort.

Do not use personal belongings without asking: Always ask before borrowing anything, such as towels, toiletries, or appliances. Respecting personal property shows consideration and builds trust.

Be respectful and polite: Treat your roommates or hosts kindly and courteously. Saying "please" and "thank you" can go a long way in building positive relationships.

Be flexible and adaptable: Living with others requires compromise and flexibility. Be open to adjusting your habits and routines to accommodate other’s needs.

Contribute to a positive atmosphere: Engage in friendly conversations, share a laugh, or occasionally cook a meal together. Having some fun together and creating a positive atmosphere can make living together enjoyable.

Following these tips can foster a healthy and enjoyable environment for yourself and others.

Consider what you will do in a crisis

Crises can arise. These can include mental health emergencies, medical issues leading to incapacity, criminal activities, violent altercations, natural disasters, etc.

Having a plan in place for these rare but significant events can provide peace of mind and ensure you are prepared to handle unexpected challenges effectively.

Here are some things to consider:

- How close is the property to emergency services in the area?

- Is there a safe place to go nearby in case your residence is unsafe?

- Do you have a safe method of transportation?

- If you needed to stay somewhere else for a few nights, where would that be? What would you bring with you?

- Do the people you are living with know your emergency contact?

Know your dispute resolution options

Your dispute resolution options differ based on the situation and the nature of the dispute.

Depending on the details of your situation, you may have the option of going to:

- The Residential Tenancies Board

- Nova Scotia Small Claims Court

- Nova Scotia Supreme Court - General Division

- Nova Scotia Supreme Court - Family Division

Tenants and subletters: The Residential Tenancy Board’s dispute resolution system is for disputes between landlords and tenants. That includes disputes between tenants and subletters. To start the dispute resolution process, either party can make an application to the Director using Form J.

More information about the dispute resolution process is in Dal Legal Aid’s Tenants’ Rights Guide.

Disputes among tenants or roommates: The Residential Tenancy Board does not resolve disputes between roommates. That includes disputes among co-tenants. Those disputes usually go to the Nova Scotia Small Claims Court.

Spouses: If you have children together or have been living together for more than 2 years, you and your partner would qualify as common-law spouses. Disputes about the family residence would go to Nova Scotia Supreme Court - Family Division.

Short-term Romantic Partners: If you don’t have children together and have been living together for less than 2 years, you cannot use the family court process. Any legal dispute would either go to Nova Scotia Small Claims Court or Nova Scotia Supreme Court - General Division, depending on the nature of the dispute.

Occupants and guests: Any legal dispute would either go to Nova Scotia Small Claims Court or Nova Scotia Supreme Court - General Division, depending on the nature of the dispute.

More Information

Where can I get more information?

Residential Tenancies Program:

- Phone: Toll-Free 1-800-670-4357 (within Nova Scotia) or General Inquiries at 902-424-5200.

- Website: Visit the Residential Tenancies Program website for detailed information and resources.

Dalhousie Legal Aid Tenants’ Rights Guide:

This guide provides detailed information on tenants' rights in Nova Scotia. It is now available on a dedicated website.

Legal Aid Nova Scotia:

Legal Aid Nova Scotia offers tenant resources. Visit their website for more information about their services.

Legal Information Society of Nova Scotia (LISNS):

Check our housing page for additional resources and information. You can also contact us with questions about the law in Nova Scotia.

Last Reviewed: July 2025

This content was made possible by financial support from the Department of Justice Canada’s Justice Partnership and Innovation Program.

Renters

Changes to the Residential Tenancies Act, Fall 2024 & Spring 2025

Nova Scotia has made some changes to the Residential Tenancy Act.

Some of the major changes include:

- Extending the rent cap to the end of 2027

- Prohibiting tenants from increasing the rent while subletting

- Shortening the timeline to evict tenants for non-payment of rent

- Giving landlords the option to evict after 3 late rent payments

- New forms for security deposit claims

This information applies to residential tenancies, meaning it applies to people who are renting a place to live. It does not apply to commercial tenancies, meaning it doesn't apply to people who are renting a space for their business or non-profit organization.

Changes, Spring 2025

The Residential Tenancies Program has produced pdf an information sheet(91 KB) and a video about these changes.

The following changes came into effect on April 30, 2025:

Rent cap extended to the end of 2027

The rent cap limiting residential rent increases to 5 percent per year has not been changed, but it will be extended to the end of 2027. A tenant's rent still can't be increased by more than 5% per year.

New timeline to evict tenants for non-payment of rent

Landlords will soon be able to begin the eviction process three full days after the tenant misses a rent payment.

Tenants then have 10 calendar days to pay their rent or dispute the eviction notice using the Residential Tenancies dispute resolution process.

This change comes into effect on April 30, 2025. For now, the standard process for evicting a tenant for non-payment of rent applies.

New grounds for evicting tenants for bad behaviour, late payments

They aren’t really new. Landlords could always apply to Residential Tenancies to evict a tenant for bad behaviour or for serious safety concerns.

The new conditions include more specifics, and will not be in effect until a later date. They say that a landlord can apply to end a tenancy if the tenant (or any guest of the tenant):

- Unreasonably disturbs another occupant or the landlord

- Is late with rent payments 3 or more times

- Causes extraordinary damage to the unit or damage to the landlord’s property

- Engages in illegal activity that is likely to:

- cause damage to the landlord’s property,

- affect the quiet enjoyment, security, safety or physical well-being of another occupant of the premises, or

- jeopardize a lawful right or interest of the landlord or another occupant of the premises.

Changes impacting land lease communities

A land lease community is one in which residents own their own home but lease the lot it is placed on, such as a mobile home park.

In a land-lease community, the landlord must:

- Establish a common anniversary date to change or implement rules (like what a tenant is responsible for on their lot); the anniversary date must be the same as the pre-established date for rental increase, if there is one

- Provide 4 months written notice before the anniversary date if they plan to change the rules

- Post a written copy of the rules or changes in a common area that all tenants can access

- Provide written copies of rules and changes to all tenants

- Post written copies of any existing landlord rules in a land-lease community in a common area accessible to all tenants and provide written copies to each tenant within 30 days of the legislative change in effect date

This change comes into effect on April 30, 2025.

Landlord’s contact Information

Landlords will have to provide tenants with the following contact information in a lease:

- name

- civic address

- mailing address

- telephone number

- email address (if one was provided by the tenant)

- contact information for the landlord and any agents like property managers or superintendents

Any changes to the contact information must be provided in writing within 30 days of the change.

For any existing leases not containing complete contact information, the tenant must be provided the complete contact information in writing within 30 days of the legislative change in effect date.

Any documents served by email must be sent from the same email address provided in the lease contact information.

This change comes into effect on April 30, 2025.

Changes, Fall 2024

New security deposit forms and claims process

Landlords need to return the security deposit within 10 days of the last day of the tenancy unless:

- there’s unpaid rent,

- there are damages to the rental unit,

- they have the tenant's written permission to keep some or all of the tenant’s security deposit.

If any of those conditions apply, the landlord can claim the security deposit by completing a security deposit claim (Form R) and sending it to the tenant.

If the tenant:

- does not receive their security deposit, or a copy of their landlord’s security deposit claim form, within 10 days of the termination of tenancy, or

- receives a security deposit claim form and wants to contest any part of it,

they can submit an application to Residential Tenancies for return of the security deposit. Residential Tenancies can make a decision resolution without a hearing.

These changes came into effect on August 1st 2024.

Subletter’s rent must be the same as the tenant’s rent

It is now illegal for tenants to sublet their units for more rent than they are paying. This change took effect on September 20th, 2024.

Last reviewed: April 2025

Owner-occupied Rentals

This page has legal information for landlords and tenants in owner-occupied rental units.

An owner-occupied rental is a residential tenancy where the landlord and tenant live together on the same property. That includes situations where a landlord rents out:

- A spare bedroom in their home.

- An in-law suite.

- A loft space.

- An outbuilding like a garden suite, bunky, or laneway house.

This page provides legal information only. It does not replace advice from a lawyer.

What you should know

The law is the same, the disputes are different

Whether the rental is owner-occupied or not, the law is the same. No special rules or conditions in the Residential Tenancies Act apply just because it’s an owner-occupied rental unit.

However, in owner-occupied rentals, the landlord and tenant tend to spend more time together, which gives more opportunity for disputes to arise. The interpersonal relationship between the landlord and the tenant tends to be critical when it’s an owner-occupied rental.

Some common sources of disputes in owner-occupied rentals are:

- Landlords making overly restrictive rules

- Landlords entering the tenant's space inappropriately

- Landlord's use of video surveillance

- Roommate chores and responsibilities (e.g. doing the dishes, taking out garbage, etc.)

- The tenant's social life (e.g. partying, staying up late watching TV, and having guests over)

While less common, crises can arise, and disputes about crisis situations can be more severe in an owner-occupied rental. That can include mental health emergencies, medical issues leading to incapacity, criminal activities, or violent altercations.

There are limits on the landlord’s ability to make and impose rules

Rules must be reasonable

A landlord can put their own rules into a lease if they don’t conflict with the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA). The landlord must give the tenant a copy of their rules when they sign their lease.

Any rule must also be “reasonable,” which means:

- It doesn’t violate the RTA or assign a landlord’s responsibilities to the tenant

- It ensures all services are fairly distributed to tenants

- It promotes the safety, comfort, and well-being of all tenants

- It protects the landlord’s property from abuse

Rules must apply to all tenants equally, and a landlord must clearly explain what tenants must or must not do to obey the rule.

Changing the rules or imposing new rules

Landlords can change rules by giving a tenant at least four months’ written notice before the lease anniversary date. If a landlord misses a tenant’s anniversary date, the new rules will only come into effect on the next anniversary date.

Tenants also have the right to ask for rules they are uncomfortable with to be changed and are under no obligation to follow an unreasonable or illegal rule after signing. However, the landlord may not acknowledge that the rule is unreasonable, which may lead to a dispute between the landlord and the tenant.

Enforcing the rules

The landlord must apply to the Residential Tenancies Program for dispute resolution to enforce a rule. It only makes sense for a landlord to impose a rule if they are willing to take that step to enforce it.

Not all rule violations are serious enough to justify eviction. Even if a rule is reasonable and there’s evidence that the tenant violated it, a Residential Tenancies Officer may give the tenant a warning rather than evict them.

Landlord’s entry and good behaviour

Both landlords and tenants have a legal obligation to behave well. This means that both parties must not interfere with the possession or occupancy of the other.

However, landlords do have a right to enter the unit they rent. While there is no limit on how often this can occur, landlords cannot use their right of entry to harass the tenant.

A landlord can enter a rental property between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. for any reason, as long as they give the tenant 24 hours’ written notice.

They can also give notice that someone else will be entering the unit, like a contractor. A landlord or tenant is not required to be present while the other person is in the unit.

The landlord cannot just give a wide range of times that they will be in the unit (e.g. they cannot say they will be there at some point between Mon-Fri between 9 am-5 pm); it must be a specific time and date.

A landlord can only enter a premises without notice in two situations:

- There is an emergency. An emergency is generally something that could cause significant damage to the property or where there is a risk to someone’s life. In these situations, a landlord (or emergency medical responder) can enter regardless of whether or not the tenant is home.

- They reasonably believe that the tenant abandoned the lease (i.e., the tenant has moved out and does not intend to pay rent or return).

Landlords are bound by federal privacy law

Landlords are required to comply with Canada’s private sector privacy law. This means they must handle tenants' personal information responsibly. With some exceptions, they must obtain a tenant’s consent when they collect, use or disclose their personal information.

Some obligations that landlords have under privacy law include:

- Identifying the reasons for collecting personal information before or during collection. The reasons given should be what a reasonable person would consider appropriate given the circumstances.

- Providing individuals with access to the personal information that they hold about them and allowing them to challenge its accuracy

- Only using a tenant’s personal information for the purposes it was collected.

- Ensuring that personal information is protected by appropriate safeguards

Privacy laws can be challenging to enforce

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada administers the relevant federal privacy law. It provides information about privacy for landlords and tenants and can receive complaints about privacy concerns in the landlord-tenant context.

However, they are often limited to making recommendations, and since they respond to complaints from many different sectors across the country, their capacity is limited.

Reasonable video surveillance is allowed

There is no specific law prohibiting reasonable video surveillance by landlords. However, landlords must comply with privacy laws and guidelines to respect tenants' privacy rights.

A landlord can use outdoor video surveillance, including door cameras, provided the monitors and recordings are secured. The best practice is for the landlord to post signs and clearly explain to the tenant when and how footage will be used.

Landlords should advise tenants of the policies before installing video surveillance.

Cameras should not capture the inside of apartments. Monitors and recorded images should be secured and only accessed for the purposes specified in the landlord’s policy.

Overnight guests

Overnight guests can cause conflict in any landlord-tenant situation, but in owner-occupied rentals it tends to be a more common source of dispute because it's easy for the landlord to know when someone else has spent the night.

This most often becomes a problem when the tenant is in a long-term romantic relationship.

Clauses or rules against having guests, including overnight guests, are usually unenforceable. However, if the guest is there so often that they’re essentially an occupant, that’s different because adding an occupant requires the landlord's consent.

The law does not set a specific number of days after which a guest can be deemed an occupant. It’s something for the landlord and the tenant can come to an agreement about.

If the landlord and the tenant end up in a dispute about overnight guests, either can apply to Residential Tenancies for dispute resolution.

Tips for tenants

Visit the property before you rent

This is a tip that applies to all tenancies. Renting a property without visiting it first is never a good idea.

There’s no right to leave a tenancy just because you feel you made a mistake.

If you abandon the tenancy, Residential Tenancies will generally award a landlord between 1 and 3 months’ rent after you have moved out, which you will be required to pay.

Visiting the property is important with an owner-occupied property because you need to consider its layout (see the next tip).

Consider the layout of the property

As you will be living with the landlord, you must consider where your space will be relative to theirs.

For example:

- Where will your room be relative to the landlord's room?

- How is the soundproofing? Will the landlord be able to hear you in your room?

- Will you have your own entrance?

- Will you have to pass the landlord's room to access common areas like the kitchen, bathroom, living room, etc.?

- If you drive a vehicle, where will you park your vehicle?

Ask about the landlord’s occupation and work schedule

As you will be living in close proximity and possibly sharing common spaces, try to understand how often you and the landlord will be in the space together.

Maybe the landlord has a different work schedule than you or doesn’t always live at the property. In these cases, there would be minimal overlap, which may reduce conflict and make the arrangement more attractive to you.

Ask to see a written list of the rules before you decide to sign the lease

A landlord can put their own rules into a lease if they don’t conflict with the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA). They must give you a copy of their rules when you sign your lease. Any rule must also be “reasonable,” which means:

- It doesn’t violate the RTA or assign a landlord’s responsibilities to the tenant

- It ensures all services are fairly distributed to tenants

- It promotes the safety, comfort, and well-being of all tenants

- It protects the landlord’s property from abuse

Rules must apply to all tenants equally, and a landlord must clearly explain what tenants must or must not do to obey the rule.

Before signing a lease, tenants should check for any overly restrictive rules. Although tenants are not obligated to follow unreasonable or illegal rules after signing the lease, overly restrictive rules can indicate that you may have problems with your landlord in the future.

Landlord rules are subject to negotiation. Tenants can ask for rules they are uncomfortable with to be changed.

Ask if the landlord uses video surveillance and, if so, where they use it

A landlord is permitted to use outdoor video surveillance, including door cameras, provided that the monitors and recordings are secured and that they post signs and clearly explain when and how they will use the footage.

Landlords should not be using video surveillance inside the unit. If they do, you should avoid renting from them.

If you’re dating someone, don’t let them sleep over every night

Adding an occupant to a rental unit requires the landlord's consent. So if you have guests over so often that it starts to seem like they live there, that may cause problems.

While there is no specific limit on how often a guest can stay before being considered an occupant, it might not be advisable for your partner to stay overnight at your unit for more than half the year.

Consider what you will do in a crisis

Crises can arise. These can include mental health emergencies, medical issues leading to incapacity, criminal activities, violent altercations, natural disasters, etc.

Having a plan in place for these rare but significant events can provide peace of mind and ensure that you are prepared to handle unexpected challenges effectively

Here are some things to consider:

- How close is the property to emergency services in the area?

- Is there a safe place to go nearby if the property is unsafe?

- Do you have a safe method of transportation?

- If you needed to stay somewhere else for a few nights, where would that be? What would you bring with you?

- Do you have a Will, a Personal Directive, and a Power of Attorney?

- Does your landlord have an emergency contact for you?

Tips for landlords

Learn the basics

Take some time to learn the basics about landlord-tenant law.

You can find information about residential tenancies on the Residential Tenancies Program website.