Get started on this section by watching this short key topic webinar.

An investment is something you get with the goal of having it grow in value over time.

This simple definition contains some basic but important financial literacy concepts.

- something you get: When you invest, you get something by giving up something you have. Usually you give up money, but you might give up your time.

- goal: When you invest, it is not a “sure thing.” Like any goal, the goal of growth might or might not be reached.

- grow in value: You invest so that you will have something worth more than what you have now.

- over time: Your investment needs time to grow. The length of time you are willing to wait could be several months or many years.

We will be talking about financial investments in this guide. But financial investments are not the only way to have something that is worth more later than it is worth now. Your house, your jewelry or even a special trading card collection can grow in value over time. Getting an education or bettering yourself in some other way are also investments. We won’t be talking about those here, but these examples can help you understand the idea of investing.

When you are thinking about investing, it is important to do what is right for you. The goal of any investment is growth in value, but only you know what you want to do with that extra money. You might want to buy a house, help your children go to university, or create a nest egg for retirement. How long you are willing to wait for an investment to grow and how much risk you are willing to take will depend on the goal. So, the way that you invest and what you invest in will also depend upon this.

Types of Financial Investments

Different types of financial investments will make your money grow in different ways:

- You can deposit your money in a bank savings account that pays you interest.

- You can loan your money out for a short or a long time and earn interest.

- You can become a part owner of a company and get a share of the money it makes.

- You can sell your share of a company for more than you paid for it.

When your money grows through an investment, that growth is called the “return on investment.”

This video gives a good overview of investing. It is from the Nova Scotia Securities Commission (NSSC), the government agency that helps to protect investors in Nova Scotia.

You can also read NSSC’s overview of investing in this blog post.

Investments Which Earn Interest

The simplest type of investment is one where you let someone use some of your money, and they pay you the full amount back plus a little bit extra. You own the money, but you’re not using it. So, you let someone else use it, and you charge them a little bit to use your money. The little bit is called “interest,” and it is your return on investment.

Examples of this type of investment include:

- a savings account in a bank

- a guaranteed investment certificate

- a government savings bond

If you are like most people, the word “interest” might make you think more about borrowing money than investing it. If you borrow money, you must pay it back. And you pay interest. Until you pay it back, you have“ debt.” It might help you to think about investments with interest as the exact opposite of debt.

In each of the examples above, the person or company on the other side of the investment has borrowed from you, the investor. The borrowers have debt because now they owe you money. You have an investment, because you are owed the money back. The amount you loan them, or invest, is the same as the borrower’s debt, or the amount the borrower owes you. In the same way, the amount of interest they will have to pay is the amount you will get. Their cost of borrowing is your return on investment.

Investments that pay interest are sometimes called “deposit-type” investments. This is because you are depositing money to make a return. Let’s talk about some examples.

When you have a savings account, you have an investment and the bank has a debt. In other words, you are loaning the bank some of your money.

If you have a guaranteed investment certificate (GIC), it is an investment to you, the owner of the GIC. It is a debt for the financial institution you got it from. Financial institutions are companies that are in the business of money and include banks, trust companies, loan companies, and insurance companies.

On the other hand, you probably know that a mortgage is a special kind of loan that you can get to buy a house. If you have a mortgage for your house, it is debt to you. But that mortgage is an investment to the bank that loaned you the money.

How Interest Works

We said interest is what you earn when you let someone borrow your money. It is also what you pay when you borrow from someone else. How much interest you will earn or pay depends on three things:

- the amount of money being loaned out or invested by the owner, known as the “principal”

- the percentage rate of interest being charged, known as the “rate,” and

- the length of time the money is loaned out or invested for, known as the “term.”

If you have ever borrowed money from a bank, you have seen these words before. As a borrower, you paid interest instead of earning it.

Interest rates are expressed as a percentage over a year. This is true even if the money is invested for days, weeks, months, or years. So, if you invest by loaning money for less than a year, you calculate the interest based on the part of a year the borrower uses the money.

Examples:

If you invest $10,000 for one year at a rate of 10 %, you will earn $1,000 in interest and have $11,000 by the end of the year. Here is how you calculate the interest:

$10,000 (the amount you invest, also called the principal) x 10 % (the interest rate) x 1 (one year, the term of the loan) = $1,000 (your return on investment). Add the return on investment to the principal ($1,000 + $10,000 = $11,000) to get the amount you are owed at the end of the year. This $11,000 is the new value of your investment. Your investment has grown by $1,000, from $10,000 to $11,000, over the year.

If you invest $10,000 for one month at a rate of 10 % interest, you will earn $83.33 in interest, and your investment will be worth $10,083.33 at the end of the month. Here is the math:

$10,000 (the principal) x 10 % (the interest rate) divided by 12 (12 months in a year) = $83.33 (the return on your investment). Why divide by 12? There are 12 months in a year and the money was invested for 1 month, so you divide by 12 to find out how interest you will earn for 1 month.

Compound Interest

Sometimes interest is paid out every month or year during the term of the investment. This is called “simple interest.” But often, interest is not paid every month or year, even though it is being earned. Instead, no interest is paid at all until the time that the original money borrowed (the principal) is paid back. In these cases, the investor is also loaning the borrower the interest on the money, and the interest becomes part of the loan and investment.

Now both the principal and the interest are earning more interest.

This is how banks calculate your interest on your savings account. In this case, you are charging your bank interest on the principal and “interest on the interest.” As the investor, you are earning interest on the interest, while the borrower is paying the same interest on the interest. When interest is earned on interest, it is called “compound interest.”

Here’s an example:

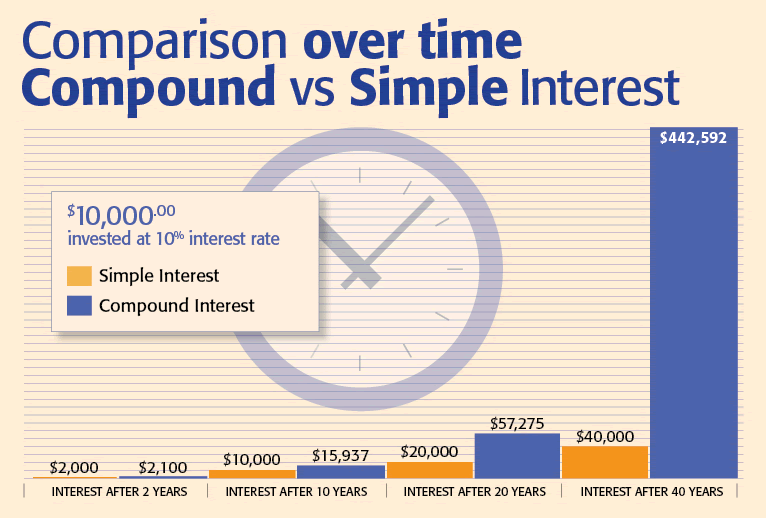

You invest $10,000 for two years at a rate of 10 % interest.

With simple interest, the math is:

$10,000 (the principal) x 10 % (the interest rate) x 2 (the number of years for the investment) = $2,000. This would happen if you were paid the $1,000 of interest for the first year rather than reinvesting it. This means your $10,000 investment earned $1,000 ($10,000 x 10 %) in the first year and $1,000 ($10,000 x 10 %) in the second year. Interest was earned on the principal amount each year, but there was no interest earned on interest because the interest was not invested.

With compound interest, the math is:

Year 1: $10,000 (principal) x 10 % (interest rate) x 1 (year) = $1,000 in interest.

If you leave the $1,000 interest invested by not having it paid to you at the end of the first year, you will have $11,000 invested for the second year.

Year 2: $11,000 (principal plus invested interest) x 10 % (interest rate) x 1 (year) = $1,100 interest.

In Year 2, you earned interest on the interest from Year 1. By leaving the first $1,000 of interest earnings invested, you earned 10 % on this amount as well as on the original $10,000.

Compounding can seriously increase the amount of interest earned over a long period of time. The longer the time you invest with compound interest, the greater the effect of compounding, and the more interest you earn.

How often the interest on interest is calculated is called the "frequency of compounding.” The more often the interest on interest is calculated, the more interest you will earn. You can try your own examples of how compound interest works using this online compound interest calculator.

The great Albert Einstein once said “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.”

Compounding works with other types of investment returns as well. If you leave your returns invested, you will earn “return on your return.” This is why people are encouraged to start saving and investing as early in life as possible.

Investments Which Earn Other Returns

Let’s say a friend wants to borrow $1,000 from you. He needs money for his small business. He could just borrow the money and pay interest, or he could ask you to invest in the business by buying shares. If you bought shares, you would become a part owner of his company. You would be making what is called an “equity investment.” In the financial world, equity is value: the value of a company or its shares. When you buy an equity investment you own part of that value. You become a shareholder of the company.

Equity investments don’t pay interest and don’t guarantee are turn at a stated rate the way a deposit-type investment does. But if the company makes money, you might earn two types of return: “dividends” while you own the shares or a “capital gain” when you sell the shares. Let’s look at both types.

First, the company might decide to pay part of their “profits” to shareholders in the form of dividends. A company makes a profit when it earns more in a year is than it uses up on expenses. Profits add up over time to become “earnings.” Dividends are a way for a company to share some of its earnings among its owners. You can earn dividends as long as you have an investment in the company, meaning as long as you own the shares.

Dividends are different from interest. The company pays dividends only if it has earnings. Even then, the company decides whether to pay dividends. If a company takes out a loan, it must pay interest whether it makes money or not. You can see that owning shares is riskier than owning an investment like a GIC or bond that pays interest. Investments that pay interest always pay interest, and always at the rate promised. Dividends may or may not be paid; it’s up to the company to decide.

The second way you could make a return on your $1,000 investment in shares of your friend’s company would be to sell your shares to someone else for more than $1,000. If you sold those shares for $1,100, you would have made a return of $100. This type of return is called a capital gain. The market for the shares of small local companies is limited, so finding a buyer might be hard or impossible.

Of course, the company may not make any profit and may not pay dividends. Worse, you may not be able to sell the shares for more than the $1,000 you paid for them.

If you sell your shares for less than $1,000, you are losing money. In the investment world, this is called a “negative return on investment,” or a “capital loss.” If the company fails, you might get nothing for your shares and could lose your whole investment.

This equity investment example involves investing in a local, small, privately held business. But most people who buy equity investments buy what are known as “publicly traded” shares. These shares are traded on a stock exchange, so they are easier to buy and sell. But the concepts and the type of return earned are the same.

Whether you own shares in a private company (shares not traded on a stock exchange) or shares in a publicly traded company (shares traded on a stock exchange), you might earn dividends or a capital gain or both.

But you might also earn no dividends or have a capital loss. This is why equity investments are riskier than investments which earn interest.

Equity investments can provide higher returns than fixed income investments, but they can also provide lower returns, including losses. It is important to carefully research and understand a company before investing in its shares.

This video is a good summary of equity investments.

Investment Funds (Mutual Funds, Exchange Traded Funds)

All equity investments are risky since you never know for sure whether any stock will be worth more or less over time. Even highly skilled professionals, including traders and financial advisors, cannot predict with accuracy how a particular stock will do in a given period of time.

But you can reduce your risk a bit. You can buy shares in several different companies, rather than counting on one or a few stocks to do well. This idea of “not putting all your eggs in one basket” is called “diversifying.”

One popular way to do this is to buy units of mutual funds or exchange traded funds. These funds are made up of shares or stocks in several different companies. Mutual funds can also be used to buy shares in foreign companies that may not be available to buy as separate shares in Canada.

These two videos explain the basics of mutual funds and exchange traded funds.

Although mutual funds or exchange traded funds can be less risky than individual stocks, you still don’t have a guaranteed return on investment. These funds can earn high returns but, like individual stocks, can also earn low returns or even lose money.

John Robertson is a scientist, author and teacher. He teaches people how to invest in a way that is easy to understand. In his presentation, Simple Investing, he explains financial investment types. Watch his video here.

You can also read this handout from the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA). The CSA is an organization that protects investors across Canada.

pdf Investments 101 CSA(402 KB)

Other Financial Investments

So far, we have talked about the basics of financial investing. If some or all of this information was new to you, you are ready to go on to the next section. If you would like more information about equity investments or more complex investments, read this brochure from the CSA.

Investments and Income Tax

In Canada, an important part of investing is understanding that you will almost always pay taxes on the income you earn from your investments. Income you earn from your investments is still income, and just as you pay tax on income from your job, or business income if you are self-employed, you pay tax on income from your investments, except in certain cases.

Investments can give you three types of income or returns on investment. These are interest, dividends, and capital gains. The government taxes each type of income differently.

So, as well as thinking about how much risk you are willing to accept when choosing investments, you must also think about how the return on investment will affect your personal income tax.

Registered and Non-registered Investment Accounts

You can invest in ways that will save money on your taxes by setting up special accounts, called registered accounts, to hold the investments that you buy. These special accounts are “registered” with the Government of Canada, meaning that the government allows you to set them up and keeps close track of them. Investment accounts which are not set up this way are called “non-registered” accounts. For example, if you went to your bank and purchased a GIC it would be held in a non-registered account unless you went through the process of setting up a registered account to hold it in.

The Government of Canada wants to encourage you and all Canadians to save or invest for the future. They offer investment programs that help you pay less tax on your investment income or pay it later. This is called giving you a “tax break.” To get these tax breaks, you must hold your investments in special accounts registered for a specific tax program.

You might have heard of an RRSP—a Registered Retirement Savings Plan. This is one type of account that might help you pay less tax. A program to help you save for the costs of education beyond high school is also available. It is called a Registered Education Savings Plan, or an RESP.

Almost all Canadians who invest use one or more of these programs. For many investors, all of their investments are held in registered accounts: none of their investments are held in non-registered accounts. This is because most investors want to take advantage of investment tax breaks as much as possible.

Although not all the programs are named as “plans,” most are, so we will use this word for all of them to keep it simple.

The three investment-related plans that Canadians use most are:

- Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP)

- Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA)

- Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP)

Although each plan has different features, what they have in common is that you can hold any type of investment product in them. For example, you can buy individuals stocks for your RRSP, but you could also buy a GIC or mutual funds for it. When you buy investments to hold under one of these plans, you first have to set up the special registered accounts to hold them.

If you think of investment products like fruits you could think of the registered accounts like special baskets. Whether the basket is an RRSP account, a TFSA account, or an RESP account, it can hold different types of investments (shares, bonds, GIC’s, mutual funds, etc.) The rest of your investment fruits, if you have more, get held in non-registered (not special) account baskets. You don’t get any special tax breaks with non-registered accounts. John Robertson allowed us to use this comparison and other information from his book,The Value of Simple. He explains investment products and investment accounts in his Simple Investing presentation. Watch his video here.

Every Canadian resident can hold one or more registered accounts for each plan. You can also have them at one or more financial institutions. For example, at one bank you could have an RRSP account that holds a GIC, and at a credit union down the street you could have another RRSP account which holds mutual funds. Both would be RRSP registered accounts and the income from the investments in them would have RRSP tax breaks. In the same way, you could have one or more TFSA accounts or RESP accounts, with several different investment products in each.

Registered Retirement Savings Plan

The Registered Retirement Savings Plan, or RRSP, has been in place since the 1950s. It encourages Canadians to save or invest for retirement. This plan allows you to subtract the amount you invest from your taxable income in the year you put the money in the plan. This means you can put off paying the tax on that income until a later date, when your income tax rate may be lower. And as long as you keep the money in the plan, you also don’t have to pay tax on the investment income earned.

When you take money out of the RRSP account, you pay tax on all the money you take out. It doesn’t matter whether you are taking out what you put in or what you earned as investment income. None of it has been taxed yet, so it will all be taxed in the year that it is taken out. This plan lets you pay tax later which is different than you not having to pay tax at all. Unlike the Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA), the RRSP is more of a “tax-later savings account.”

This explanation just touches on the rules for RRSPs. There are many others, including how much money you can put in your RRSP in each tax year and rules that allow you to take money out for special purposes without having to pay the tax until later. One such special purpose is the down-payment on your first home.

This blog post tells you more about RRSPs.

A registered account related to the RRSP is the Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF). The money in your RRSP must be moved to an RRIF account no later than the year you turn seventy-one. A certain percentage of your RRIF must be withdrawn and taken into taxable income each year from that point on.

This blog post tells you more about RRIFs.

Registered Disability Savings Plan

The Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) is a plan to help Canadians with disabilities be prepared for their financial future. Money can be invested into an RDSP account by the individual, family members or others. No tax is owed on the investment income while the money is in the plan. The Canadian Disabilities Savings Grant (CDSG) and the Canadian Disabilities Savings Bond (CDSB) are parts of the plan where the government puts money into the account. The eligibility rules are different for each part of the plan but both involve being below certain income levels. There are also age limits for eligibility.

If you or a family member may be able to benefit from this plan, find out more information from the government’s website.

https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/disability/savings.html

Tax-Free Savings Account

Of all the plans that can help you with your taxes, the simplest to understand and use is the Tax-Free Savings Account, or TFSA.

Although it is called the Tax-Free Savings Account, it might be better named the “tax-free investment plan.” An investor can hold many different investment products in accounts registered under this plan, not just “savings.” And they don’t ever pay tax on the income their investments earn. That is the “tax-free” part.

The TFSA is different from an RRSP because you pay tax on the money you put in, or “contribute to,” a TFSA. But you never pay tax on the investment income you earn. You don’t get to put off paying taxes on the amount you put in as you do with an RRSP. But you also don’t pay any taxes when you take money out of the account. This is because you already paid tax on the money that went in, and the investment income is tax-free.

This blog post tells you more about TSFAs.

Registered Education Savings Plan

The Registered Education Savings Plan, or RESP, allows you to put off paying taxes on investment income until the money is used to pay for education costs. Usually the plan is for your child’s education, but it could be for another family member or for yourself.

In addition to letting you put off paying some income tax, the RESP lets your child, or the student whose education is paid for, pay the tax on any income from the investment. Students usually pay less income tax than the people who saved for the education program. This is good for both the investor and the student. For example, instead of you paying $3,000 in tax on $10,000 of investment income, your child gets to pay a much smaller amount of tax or maybe none.

An RESP account has another even bigger bonus: the government will give you up to $1 for every $5 you contribute to the account through a grant program called the Canada Education Savings Grants (CESG). This is like getting a guaranteed 20% return on most, if not all, of the money you put in! Some families may also be able to get grants called Canada Learning Bonds (CLB).

This blog post and this video tell you more about RESPs.

John Robertson reviews the main Canadian tax-registered account types in his Simple Investing presentation. Watch his video here.

The following infographic and comparison document show the differences between RRSPs and TFSAs.

Other Registered Plans

The Government of Canada has detailed information on all of the registered savings and investment plans at the Canada Revenue Agency website.

https://www.canada.ca/en/services/taxes/savings-and-pension-plans.html

Risk and Return

Risk and return always go together when you invest, and not always in the way we would like. There are no guaranteed high returns: To get the chance of a higher return, you have to take on more risk. This means you might or might not get the high return you want. If you want low risk, or more of a “sure thing,” you must accept lower returns.

Risk and Interest Rates

We talked about investments which pay interest being called deposit-type investments. They are also referred to as “fixed-income investments.” This means the return is “fixed” or set at an agreed-upon interest rate. The timing of both compounding and payout are also set before you invest. This type of investment is the least risky in one way: as the investor, you know how much interest or return you will earn.

But that doesn’t mean there is no risk: the borrower may not pay you either the interest earned or the original amount you invested. When the borrower doesn’t pay what they owe to the investor, it is called “defaulting.” This type of risk is known as “default risk” or “credit risk.”

How risky an interest-type investment is, depends on the borrower and the situation. A bank is less likely to default on a loan than a person, and some people are less likely to default than others.

For example, you might loan money for a trip to a friend, who has no job. That is riskier than loaning money for buying a house to a friend who has a job. The house (which could be sold) and the job (which brings money in) mean this friend is more likely to have the money to pay you back than the friend with no job who spent the money on a trip.

Default or credit risk is important to both investors and borrowers because it affects the rate of interest.

For example, if you buy a $1,000 GIC investment from a bank with a rate of 3 %, your risk is extremely low. First, the rate of return is fixed at 3 %. Second, you will certainly receive both the interest promised and the principal back. This kind of investment has almost no risk to you. You know the amount you will get because the interest rate is fixed, and you know that you will get it because banks are reliable.

On the other hand, you making a $1,000 investment as a personal loan to a friend is much riskier. The friend might not pay the 3 % return they promised and they might not pay back the $1,000 investment. That is, your friend might default on one or both amounts.

Although the amount you should get back is certain and identical in both cases, the risk of whether you will get it back is very different.

Given this, you would probably prefer to invest your $1,000 into the GIC. But what if the friend agreed to pay you 10 % interest instead of 3 %? Even though loaning to the friend is still riskier, you may be willing to invest with the friend because the promised return is higher. Different degrees of default or credit risk result in different interest rates.

When banks invest by loaning you money, they look at these risks. This is why the interest rate on your mortgage is less than on your personal loan. It is also why someone with a good income and track record of paying off their debts can get a bigger mortgage with a lower interest rate than someone with a lower income and poorer track record.

In order to earn higher returns, an investor must accept higher risk. This is the basic idea of risk and return for all investments. This video explains this idea using the example of bond investments.

Risk and Equity Returns

Unlike interest, the return on equity investments is not fixed at all. For this reason, equity investments are riskier than fixed-income investments. When you own individual stocks (or units of mutual or exchange traded funds), there is no promise that you will be paid dividends and you might not earn a capital gain. Some companies, such as big banks, have paid dividends every year for many years. It is likely these companies will continue to pay dividends on a regular basis. Investors looking for regular monthly income in retirement often hold these “dividend stocks” specifically for that purpose. But it is never one hundred percent certain that dividends will be paid by any company.

You might wonder why you would even think about buying these riskier investments. The answer, of course, has to do with risk and return. You may think of the risk as being bad, but risk is just uncertainty: it can be bad or good.

You might not get dividends and your investment might be worth less when you sell it than it cost. But remember, this is a “might” situation, not a sure thing. Maybe you will be paid dividends and maybe you will sell the investment later for much more than it cost. So, your overall return might be much higher than you could get with a fixed-income investment. You might make a lot of money, you might make no money, and you might lose some or all of your original amount invested or principal. This is what risk is, and it is directly tied to return.

The same way that you might be willing to take on more default risk to get that 10 % interest, rather than 3 %, you might also want to take a chance at earning higher returns from equity investment rather than sticking to only fixed income investments. But with the risk of the higher returns, comes the risk of lower or no returns and the risk of losing some or all of your principal.

We talked earlier about reducing some risk by diversifying. Rather than putting “all your eggs in one basket,” by investing in one or two stocks, you can diversify and buy funds (mutual funds or exchange traded funds) containing many stocks. While this strategy does reduce your risk (because some stocks in the fund might go up and some might go down), there is still risk that the overall value of the fund could go either up or down, a little or a lot.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to how much risk you should take on make you invest. You must decide how much risk you comfortable you are with. This is known as your risk tolerance. Your risk tolerance will not always be the same. It will depend on your personality but also on your financial circumstances, your age, stage of life and investment goals.

The second section of this guide is about your rights as an investor. What you learned in this first section about the basics of investing will help you understand your rights.